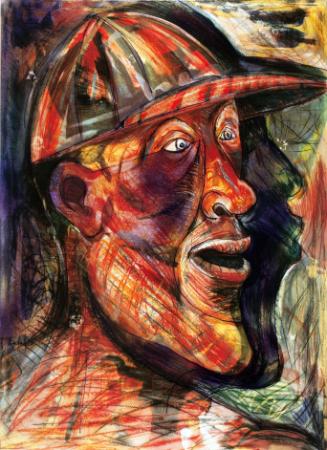

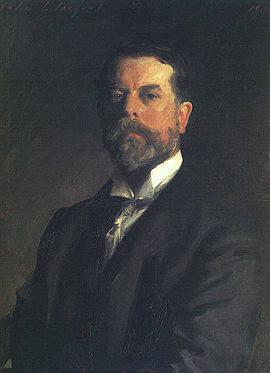

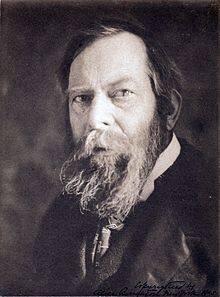

Henry Ossawa Tanner

American, 1859 - 1937

Birth-PlacePittsburgh, PA

Death-PlaceParis, France

BiographyHenry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937)Henry O. Tanner, African-American painter and printmaker, was born in Pittsburgh. He was the son of Sarah Miller, a freed slave, and Benjamin Tucker Tanner, a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the editor of the “Christian Recorder”. Tanner's parents were strong civil-rights advocates, which accounts for the fact that his middle name, Ossawa, was a tribute to the abolitionist John Brown of Osawatomie.

In 1868 the Tanner family moved to Philadelphia, where Henry saw an artist at work in Fairmont Park and decided immediately to become one. His mother encouraged this ambition, though his father apprenticed him in the flour business after he graduated, valedictorian, from the Roberts Vaux Consolidated School for Colored Students in 1877. Flour work proved too strenuous for Tanner and he became ill. After his convalescence near John Brown's farm in the Adirondacks in 1879, he entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and studied under Thomas Eakins, and Thomas Hovenden was his mentor. Tanner's professional career began while he was still a student. He made his debut at the Pennsylvania Academy annual in 1880, that year he also exhibited at the Progressive Works Men's Club in Philadelphia, the first exhibition ever of African-American artists organized by African Americans. During this period he specialized in seascape paintings such as “Point Judith” (ca. 1880; private collection), while also rendering memories of his Adirondack sojourn, as evinced by “Burnt Pines: Adiron¬dacks” (ca. 1880; Hampton University Museum, Va.). A tendency to use overlapping shapes and diagonal lines to create recession into space was announced in these works and can be seen over his entire career. The rich browns, blues, blue-greens, and mauve, with accents of bright red, in these pictures also remained constant in his oeuvre.

During the mid-1880s Tanner decided to become an animal painter. A superb example of this genre is “Lion Licking Its Paw” (1886; Allentown Art Museum, Pa.). In addition to easel paintings, Tanner provided illustrations for short stories for the July 1882 issue of Our Continent and the January 10, 1888, “Harper's Young People”.

In 1889 Tanner opened a photography studio in Atlanta. After this business failed, he remained in that city and taught drawing at Clark University, where he met Bishop and Mrs. Joseph Crane Hartzell. They arranged Tanner's first solo exhibition, in Cincinnati in 1890, to help the young artist raise funds for European study. Tanner set sail for Italy on January 4, 1891, but after reaching Paris he decided to remain there. He enrolled in the Académie Julian, where his teachers were Jean-Paul Laurens and Jean-Joseph Benjamin Constant. He made Paris and Trépied, France, his permanent homes for the rest of his life.

Tanner visited the United States in 1893 and concentrated on sober sympathetic depictions of African-American life to offset a history of one-sided comic representations. “Banjo Lesson” (1893; Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Va.), in which an older man instructs a young lad, is the first painting that can be ascribed to Tanner's new desire. He debuted at the Paris Salon of 1893 with this painting.

At the turn of the century, Tanner devoted himself almost exclusively to biblical scenes, a result of both his devout family background and the economic opportuni¬ties provided by the subject. Almost all Tanner's biblical themes centered around ideas of birth and rebirth, both physical and spiritual. Tanner expressed his upbringing in the fledgling civil-rights movement through these themes that relate to Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which promised freedom or "birth and rebirth" to black slaves. This approach was also consistent with Tanner's desire to render sympathetic depictions of African Americans.

Tanner's relatively few portraits brought to the fore images of individuals involved with civil rights and other humane concerns. Stylistically, the portraits are characterized by a very shallow recession into space or a certain flatness, while maintaining the rich brown, blue, blue-green, and mauve palette spiked with bright reds and multiple light sources. These characteris¬tics are particularly notable in his genre scenes based on visits to North Africa in 1908 and 1912.

Frustrated by World War I, Tanner stopped painting and instead became a major figure in the American Red Cross. He resumed his career as artist on November 11, 1918, the very day of the Armistice, when the American Expeditionary Force authorized Tanner's travel to make sketches of the front, such as “Canteen at the Front” (1918; Ameri¬can Red Cross, Washington, D.C.). Tanner's mature style was characterized by experiments with thickly built up enamel-like surfaces, seen in one of his last paintings “Disciples Healing the Sick” (c. 1930; Clark Atlanta University Collection of African-American Art, Atlanta).

Tanner garnered ample recognition in the international art literature of his time and exhibited frequently on both sides of the Atlantic. He received a gold medal at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco and the prestigious Cross of the Legion of Honor in 1923. He was elected a member of the American Negro Academy, Washington, D.C., in 1898; associate and full academician of the National Academy of Design, New York, in 1909 and 1927, respectively. It would be impossible to imagine the generation of African-American artists who contributed to the Harlem Renaissance without the example of Tanner's single-minded pursuit of artistic success and his international recognition.

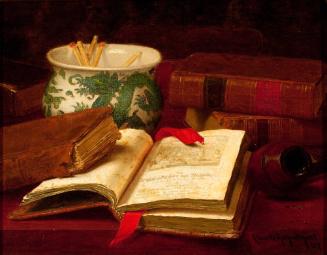

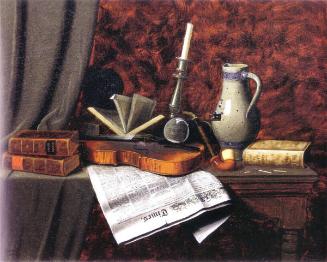

Wynkoop House, Old Haarlem, 1888

Oil on canvas, 18 1/2 x 13 1/4 in. (47 x 33.7 cm)

Signed and dated (lower left): H. O. Tanner / 1888

John Butler Talcott Fund (1984.86)

“Wynkoop House, Old Haarlem” represents a frequently misunderstood aspect of Tanner's oeuvre. Along with his characteristic biblical subjects, the artist depicted specific sites and buildings that have erroneously been seen by some writers on Tanner "as diversions from the intense work of composing elaborate biblical subjects intended for the Salon."(1)1 Recent research, however, has demonstrat¬ed that subjects such as “Wynkoop House” were important to the core of Tanner's symbolic civil-rights messages.

At first glance, the title of our painting, “Wynkoop House, Old Haarlem”, suggests that the building is in the Netherlands. However, a Wynkoop House also known as Vredens-Hof and Vrendens Berg existed at Northha¬mpton Township in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, not far from Tanner's home in Philadelphia.(2)2 It was built in 1739 by Nicolas Wynkoop, who named the place Vrendens-Hof, "abode of peaceful rest."(3)3 "When a house is distin¬guished by association with such sturdy and loyal characters as Vrendens-Hof has been, it assumes a greater dignity; Washington, Lafayette, and James Monroe having been guests, under its hospitable roof at the same time, at the close of the American Revolution."(4)4 When it was owned by George Washington's abolitionist friend Judge Henry Wynkoop5 the house would have been of interest to Tanner because Judge Wynkoop "treated his slaves so well that although he gave them their freedom, most of them remained on the farm and upon their deaths, according to legend, were buried under a tree" near Vrendens-Hof.(6)6 Tanner emphasized the tree in the foreground of “Wynkoop House” and by so doing gave it the type of social underpin¬ning found in his other site-specific works.

Although Tanner's building is in basically the same architectural style as published photographs of Wynkoop House, it does not match exactly with any section of the mansion, even when remodeling is taken into consideration.(7)7 On the other hand, an illustration in a book on Vredens-Hof published in 1908 shows individual, unattached structures on either side of the manse and behind it that call to mind the configuration at Washington's estate in Mount Vernon.(8)8 In point of fact, Tanner's rendition of Wynkoop House may be seen as a sophisticated architectural version of the slave quarters at Mount Vernon.

Stylistically, Tanner's approach in “Wynkoop House” is inconsistent with his working method in the late 1880s, as is the signature. The painting does not echo the drawing skill or spatial arrangement of the 1888 illustration “It Must Be My Very Star” and does not bear the monogram signature.(9)9 Moreover, the treatment of Wynkoop is far removed from the confident handling of “Lion Licking Its Paw” (1886; Allentown Art Museum, Pa.). The overall style of the picture, however, is perfectly consistent with Tanner's treatment in “Boy and Sheep Lying under a Tree” (1881; private collection). The middle-ground compositions and palettes of these works match up very well. Even more compelling is the dabbled sparkling light in both works which presages one of the most beautiful aspects of Tanner's mature style.

DFM

Bibliography:

Henry O. Tanner, "The Story of an Artist's Life," “World's Work” 18 (June, July 1909): 11661-66, 11769-75; Marcia M. Mathews, “Henry Ossawa Tanner, American Artist” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969); Dewey F. Mosby and Darrel Sewall, “Henry Ossawa Tanner”, exhib. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art; New York: Rizzoli, 1991); Dewey F. Mosby, “Across Continents and Cultures: The Art and Life of Henry Ossawa Tanner”, exhib. cat. (Kansas City, Mo.: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art), 1995.

Notes:

1. Mosby and Sewall, “Henry Ossawa Tanner”, p. 132.

2. Julian G. Hammond Jr., “Vrendens-Hof: A Few Facts Concerning the History of an Old House” (Frankford, Pa.: Julian G. Hammond 3rd, 1908), p. 2.

3. Ibid., p. 3.

4. Ibid., p. 2.

5. Virginia B. Geyer, "Further Notes on Henry Wynkoop," “Bucks County Historical Society Journal” 1 (fall 1976): 1-12.

6. Ibid., p. 8.

7. See reproductions in Ibid.

8. Hammond Jr., Vrendens-Hof, fronticepiece.

9. Reproduced in Mosby, “Across Continents and Cultures”, p. 25.

Person Type(not assigned)