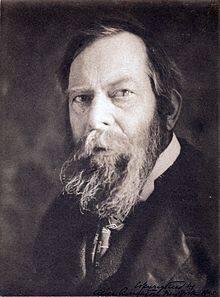

Albert Pinkham Ryder

Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

Born and raised in New Bedford, Massachusetts, Albert Pinkham Ryder moved to New York City as a young man. In addition to studying with portrait painter William Edgar Marshall, Ryder took classes at the National Academy of Design and began exhibiting there in 1873. By the 1880s his work was being sought after by a small circle of collectors and admirers. Although he came to be known as an eccentric recluse, Ryder had many artist friends, traveled to Europe several times, exhibited with such groups as the Society of American Artists, and participated in the New York art scene in the last decades of the century. In addition to lyrical landscapes, Ryder painted subjects from a variety of literary sources, including Shakespeare, Wagnerian operas, the Bible, and English Romantic poetry, and his visionary pictures of moonlit seas inspired contemporary comparisons to Herman Melville and Walt Whitman.

After 1900, though nearing the end of his career, Ryder continued to inspire younger artists. At the 1913 Armory Show, he was the sole American, along with such European masters as Van Gogh, Cezanne, and Gauguin, to be honored as a major influence in the development of modern art. A memorial exhibition was held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art upon his death in 1917, after which his reputation continued to grow. In 1930 he was named to the ranks of American masters with the historic exhibition “Winslow Homer, Albert P. Ryder, and Thomas Eakins” at the Museum of Modern Art.

Woman and Staghound (Landscape and Figure, Geraldine, Chatelaine with Greyhound), ca. 1883

Oil on gilded wood panel, 11 3/8 x 5 7/8 in. (28.9 x 14.9 cm)

Signed and inscribed (verso): A. P. Ryder / 80 E. Wash Sq / Benedick / A W

Harriet Russell Stanley Fund (1946.26)

Albert Pinkham Ryder, who was described as having "the highest, most chivalrous, but for the most part silent, admiration for women," painted several poetic interpretations of them in landscapes.(1) “Woman and Staghound” is an interesting, richly colored example of this type. The figure, dressed in a deep red Elizabethan-style gown, stands holding a leash or garland of some sort and looks down at a dog that returns her gaze with upturned head. A tall tree frames the composition at the right and its frothy branches and a distant hill enclose a glowing sky at the upper left.

“Woman and Staghound” dates from the 1880s, when Ryder moved away from pastoral landscapes and began painting more imaginative themes, literary subjects, and moonlit seascapes. The painting has been known by several titles, including “Chatelaine with Greyhound” and the more general “Landscape and Figure”.(2) The collector and poet, Charles Erskine Scott Wood, Ryder’s friend who purchased the painting in 1886, exhibited it with the title “Geraldine”.(3) Elizabeth Broun has identified Geraldine as Lady Elizabeth Fitzgerald, the subject of a sonnet by Henry Howard, earl of Surrey, a member of Henry VIII's court, an innovative poet, and ultimately a tragic victim of court politics.(4)

Literature was only a starting point for Ryder, not a narrative framework for his paintings. Except for the historic costume, there is little correspondence between the image and the specific passages from the original Howard poem, "A Description and Praise of His Love Geraldine."(5) Instead, the painting evokes the popular legend surrounding the poem and its author. When he wrote the poem, Howard was nineteen and married, and Geraldine was only a child of nine. Howard was executed in the Tower of London shortly before his thirtieth birthday and became a romantic hero in English literature, and Geraldine came to be known as the English equivalent of Petrarch's Laura or Dante's Beatrice--that is, the subject of veneration from afar and a source of creative inspiration. Ryder, who worked only when the mood struck, believed in the concept of the inspirational muse and painted several works featuring classical Greek Muses and Pegasus. He also composed his own poems in an untrained style derived from the English romantic tradition, and he considered painting to be the equal of poetry as a vehicle for lyrical expression.(6)

Possible pictorial prototypes for Ryder's image include eighteenth-century English portraits of gentlewomen with pets and hunting hounds and late-nineteenth-century revivals of this convention.(7) Yet Ryder departed significantly from this aristocratic portrait tradition. The figure does not have the prominence of a portrait, particulars of the woman's face and costume are muted, and the figure is subservient to the landscape. As in Ryder's other paintings featuring women and animals, including “Diana” (ca. 1880; Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Va.) and “Joan of Arc” (ca. 1888; Worcester Art Museum, Mass.), the dog strikes a natural pose and looks more like a common hunting dog than rare pure breed. Rather than a formal image of elegance and grace, “Woman and Staghound” is more of a vehicle for the imagination--dark, mysterious, at the same time oddly spontaneous-looking, an eerie evocation of a bygone age.

“Woman and Staghound” can also be seen as part of Ryder's work on several decorative commissions in the 1870s for the New York firm of Cottier and Inglis, including fire screens and a mirror frame.(8) Like his screens, which are of gilded leather, “Woman and Staghound” has a layer of gold leaf under its thick surface of paint and glazes. In addition, its tall narrow format and the costume-piece nature of the subject, relate the painting to Ryder’s decorative output. Even before time took its toll in darkened pigment and distorting cracks, the painting had an unusual surface that one writer called a "peculiar finish" like a piece of "old Italian enamel."(9) It was this same interest in surface and pure design that led Ryder to the brink of abstraction and attracted an entire following of admirers in the twentieth century.(10)

ET

Bibliography:

Henry Eckford, pseud. (Charles De Kay), "A Modern Colorist," “Century Magazine” 40 (June 1890): 250-259; Lloyd Goodrich, Albert Pinkham Ryder: “Centenary Exhibition”, exhib. cat.(New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1947); Lloyd Goodrich, “Albert P. Ryder” (New York: Braziller, 1959); William Innes Homer and Lloyd Goodrich, “Albert Pinkham Ryder, Painter of Dreams” (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989); Elizabeth Broun, “Albert Pinkham Ryder”, exhib. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1990).

NOTES:

1. Charles de Kay, as quoted in Goodrich, Albert Pinkham Ryder, p. 30.

2. Charles De Kay used the title “Chatelaine with Greyhound” in 1886 ("An American Gallery,” Magazine of Art 9 [1886]: 247).

3. Broun (Albert Pinkham Ryder, p. 81) correctly questions the origin of the Geraldine title, concluding that in any case, it was "Ryder's intended subject."

4. Ibid., p. 312.

5. “A Description and Praise of His Love Geraldine,” in Ray Lamson and Hallett Smith, eds., The Golden Hind: An Anthology of Elizabethan Prose and Poetry, (New York: W. W. Norton, 1956).

6. On Ryder's beliefs in the relationship between poetry and painting, see Homer and Goodrich, Albert Pinkham Ryder, p. 52.

7. Broun, Albert Pinkham Ryder, pp. 61, 313.

8. On Ryder's decorative output, see Broun, Albert Pinkham Ryder, pp. 42-55, and Homer and Goodrich, Albert Pinkham Ryder, pp. 23, 24.

9. "The Autumn Exhibition of the National Academy," Boston Daily Evening Transcript, October 22, 1883, pp. 3-4.

10. Ryder's admirers included such early modern innovators as Marsden Hartley and Arthur Dove and later abstract painters, such as Jackson Pollock. Broun (Albert Pinkham Ryder, pp. 164-79) and Homer and Goodrich (Albert Pinkham Ryder, pp. 95-116) discuss his appeal to and affinities with modern art.