Ralph Earl

American, 1751 - 1801

Death-PlaceBolton, CT

Birth-PlaceLeicester, MA

BiographyRalph Earl (1751-1801)Born in Leicester, Massachusetts, Ralph Earl was the son of farmers Ralph and Phebe Wittemore Earll. In 1774, determined to become a painter, Earl turned his back on his agrarian roots and established himself as a fledgling artist in New Haven, Connecticut.

Earl executed a number of portraits of leading patriots in New Haven, including his early masterwork Roger Sherman (ca. 1775; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven), which demonstrate his admiration for, and emulation of, the colonial portraits of John Singleton Copley. Earl also collaborated with engraver Amos Doolittle, a New Haven colleague, producing sketches for four engravings of the 1775 Battle of Lexington and Concord that are among the first historical prints in America. Despite his seemingly patriotic endeavors, Earl declared himself a Loyalist, and in 1777, with the assistance of a young British officer, Captain John Money, he fled to England.

During his eight-year stay in England, Earl divided his time between Norwich, the site of Captain Money's country estate in the province of East Anglia, and London. His early years were spent painting portraits for the Norwich country gentlefolk. By 1783 Earl was part of the entourage of American artists in the London studio of Benjamin West, where he absorbed the British portrait tradition. Earl's highly accomplished London and Windsor pictures, many of which he exhibited at the Royal Academy, demonstrate a variety of British portrait forms, including military portrayals and sporting pictures, and demonstrate Earl’s growing interest in landscape art, evident in his scenic backgrounds.

Earl became the first of West's students to return to America after the establishment of peace. In 1785, with his second wife, Ann Whiteside Earl (1762-1826) of Norwich, Earl settled in New York City. However, his ambitious start came to a sudden halt when, unable to repay a modest debt, he was confined in a debtor's prison from September 1786 until January 1788. The members of a recently formed benevolent organization, the Society for the Relief of Distressed Debtors, composed of the most illustrious New York families, came to the artist's aid by allowing him to paint portraits of themselves, their families, and their friends while he was still in prison. With such elegant works as “Mrs. Alexander Hamilton” (1787; Museum of the City of New York), as well as a series of portraits of recent heroes of the American Revolution, he earned enough money to obtain his release.

Until this point, Earl’s ambition to succeed as an artist, against all odds, had led to a downward spiral in his personal life of imprisonment, alcoholism, and bigamy. (He married his second cousin Sarah Gates in 1744; though she bore him two sons, the couple lived together for only six months before he deserted her to go to England in 1777). His court-appointed guardian, Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell, convinced Earl to leave New York and follow him to Connecticut, where Cogswell provided him with portrait commissions. Earl regained stability for himself and his family, which now included two children, plying his trade as an itinerant artist in this agricultural setting. He found his greatest success in this region, where, with Cogswell's impressive connections, he painted from 1788 to 1798.

In his Connecticut portraits, Earl cleverly tempered his academic style to suit his subjects’ modest pretensions. He abandoned the formal qualities of his English and New York portraits in favor of more realistic depictions of his subjects' likenesses and surroundings, including their attire, locally made furnishings, newly built houses, regional landscape features that celebrated land ownership, and emblems of the new nation. In addition, Earl adapted a more simplified technique, using broad brushstrokes and favoring primary colors--pigments that were more widely available in the remote regions in which he worked.

Earl was one of the few American artists in the 1790s to receive commissions for landscapes, an art form that was just beginning to take on an artistic and intellectual significance in the young nation. He had already contributed to the development of the genre in New England by including regional landscape features in his portraits, thus establishing a taste for landscape among his sitters. By 1796 he began receiving a number of commissions for landscapes showing his patron's newly built houses.

In 1798 Earl left Connecticut, moving to Vermont and Massachusetts in search of commissions. One reason for this move may have been that the popularity of his portraits engendered a number of gifted imitators who, by virtue of their less expensive prices, began to compete with Earl for commissions.

In 1799 Earl became the first American artist to travel to Niagara Falls, where he made sketches of the "stupendous cataract." After this arduous journey, Earl returned to Northampton, Massachusetts, where he produced a panorama (whereabouts unknown) of the falls that measured approximately fifteen by thirty feet. With great fanfare, the panorama was first placed on public view in Northampton, and subsequently in New Haven, Philadelphia, and London.

In 1801 Earl traveled to Bolton, Connecticut, where he died at the home of Dr. Samuel Cooley. The cause of death was listed as "intemperance."

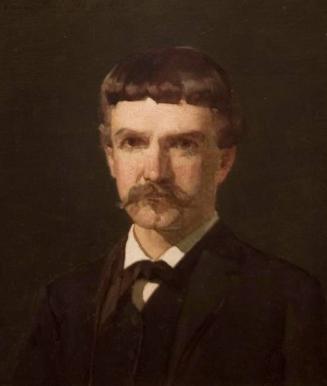

This portrait of an unidentified gentleman and his black servant has been assigned to Ralph Earl on the basis of style. Earl commonly signed and dated his portraits. While this canvas is unsigned, its edges may have been trimmed during lining, which may explain the absence of a signature. (1) William Sawitsky, an early scholar of American art who studied Earl's work in the 1930s and 1940s, first suggested that this portrait was by Earl and related it to the artist's New York period. (2)

During his career, which spanned the years before and after the Revolution, Earl modified his portrait style to suit the changing tastes of his subjects--dictated partially by their altered status after the war, as citizens of a new nation, and by the different regions in which he worked, from such urban centers as New York City to rural Connecticut towns. “Gentleman with Attendant” relates stylistically to the society portraits that he painted during his confinement in debtor’s prison in New York. There are approximately twenty portraits by Earl from the prison years, 1786 to 1788. For these works, the artist drew upon the lessons he had learned in London, painting distinguished likenesses of his elite subjects. In most instances, the compositions are simple, devoid of decorative details. The artist was likely provided with a room in the prison in which to paint but had to rely on his imagination for props. (3)

In “Gentleman with Attendant”, Earl presents his distinguished subject in fashionable attire, including a green coat with an elaborately embroidered floral silk vest with gold trim. The gentleman wears his own powdered hair rather than a wig; powder can be seen on the collar of his coat. He is seated in a red brocade armchair, placed against a plain dark background. In contrast, the gentleman's servant (or possibly slave), dressed in a red coat with a white collar, is placed against a light background. (Earl first employed the device of a two-toned wall as background in several of his English portraits. (4)) In this sensitive portrayal, the boy leans deferentially toward his master, extending a card in his left hand. While the gentleman confidently meets the viewer’s gaze, the young boy stares faithfully toward him. His mouth is open, revealing his teeth, not a gesture that was appropriate for members of eighteenth-century society. Through these details of gesture and pose, Earl differentiates the social status of his two subjects, adhering to traditional British standards of social hierarchy.

The inclusion of a black servant is rare in eighteenth century American portraiture. Other examples include Justus Englehardt Kuhn's “Henry Darnall III as a Child” (ca. 1710; The Maryland Historical Society) and John Hesselius, “Charles Calvert” (1761; Baltimore Museum of Art). As Elizabeth O'Leary has stated, "The portrayal of black servants in American art was built on British traditions of representing slaves as docile attendants, figures who functioned primarily to elevate the importance of white subjects." (5) This is the only known instance in which Earl included a black subject in his work.

EMK

Bibliography:

William and Susan Sawitsky, "Two Letters from Ralph Earl with Notes on His English Period," “Worcester Art Museum Annual 8” (1960): 8-41; Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, "Ralph Earl as an Itinerant Artist: Pattern of Patronage," in Peter Benes, ed., “Itinerancy in New England and New York: Annual Proceedings of the Dublin Seminar for New England Folk Life 1984” (1986): 172-90; Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, “Ralph Earl: Artist-Entrepreneur”, Ph.D. diss, Boston University, 1988; Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser et al., “Ralph Earl: The Face of the Young Republic”, exhib. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991); Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, "By Your Inimitable Hand": Elijah Boardman's Patronage of Ralph Earl," “American Art Journal 23”, no. 1 (1991): 4-20.

“Gentleman with Attendant (Gentleman with Negro Attendant)”, ca. 1785-88

Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (78.1 x 65.4 cm)

Harriet Russell Stanley Fund (1948.6)

Notes:

. For a discussion of Earl’s New York portraits, see Elizabeth Nankin Kornhauser, with Richard L. Bushman, Stephen H. Kornhauser, 2. The painting was lined by Roger Dennis in 1969; see paintings files NBMAA.

3. William and Susan Sawitsky Papers, New-York Historical Society, New York. In his papers Sawitsky discusses this portrait, assigning it a date about 1886; however, he never published it as a work by Earl.

4. For a discussion of Earl’s New York portraits, see Elizabeth Nankin Kornhauser, with Richard L. Bushman, Stephen H. Kornha and Aileen Dibeiro, Ralph Earl: The

Face of the Young Republic exhib. Cat. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press; and Hartford: Wadsworth Athenaeum, 1991) pp. 30-39

5. Examples include “William Carpenter and Mary Ann Carpenter” (1779; Worcester Art Museum) and “Lady Williams and Child” (1783; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); see Kornhauser et al., “Ralph Earl”, pp. 25, 116-17.

6. Elizabeth L. O'Leary, “At Beck and Call: The Representation of Domestic Servants in Nineteenth-Century American Painting” (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996), p.

Person Type(not assigned)

American, 1834 - 1903