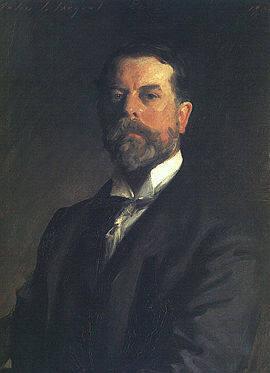

John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)

Born in Florence, Italy, to Philadelphia physician FitzWilliam Sargent and his wife, Mary Newbold Singer, John Singer Sargent enjoyed a childhood marked by extensive travel on the Continent. By the time he was eighteen he had studied with German-American landscapist Carl Welsch, English portraitist Joseph Farquarson, and at the Accademia della Belle Arti, Florence. In 1874 he went to Paris and trained under Adolphe Yvon at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and in the ateliers of Léon Bonnat and of Charles-Emile Auguste Durand (called Carolus-Duran), who is accorded the greatest credit in shaping Sargent’s early style. In Paris, Sargent became familiar with both academic tradition and emerging avant-garde styles. His social milieu encompassed friendships with a number of American art students, including J. Carroll Beckwith and J. Alden Weir, and with such illustrious international figures as James McNeill Whistler, Giovanni Boldini, Henry James, and Claude Monet.

Sargent made his first trip to the United States in 1876. Although he staunchly maintained an American identity throughout his life, he continued to reside abroad, exerting his presence in America mainly through exhibitions of his work and intermittent trips to fulfill commissions. By the late 1870s Sargent was exhibiting at most major venues, including the Paris Salon, the London Royal Academy, and the National Academy of Design, New York. He also showed with such liberal organizations as the Society of American Arts and the New English Art Club.

In the wake of critical turmoil surrounding the exhibition of “Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau)” (1884; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) at the 1884 Paris Salon, Sargent spent considerable time in England, where he ultimately established residence in 1886. In the mid- to late 1880s he summered in various rural English villages, among them Broadway, Worcestershire, home to an art colony that included Americans Frank Millet and Edwin Austin Abbey and was frequently visited by Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Henry James. These summers marked Sargent’s first intensive exploration of plein-air painting, resulting in some of his best-known canvases: “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose” (1885-86; Tate Gallery, London) and “An Out-of-Doors Study” (“Paul Helleu Sketching with His Wife”) (1889; Brooklyn Museum of Art).

By 1893 Sargent had become one of the most highly acclaimed society portraitists in England and America. Yet in spite of the demand for his portraits, he dedicated considerable time to landscape subjects and complex decorative projects, mainly murals for the Boston Public Library (commissioned in 1890, the last panels installed in 1916) and for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, commissions he researched in Palestine and North Africa. An inveterate traveler, Sargent apparently never set down his brush, as witnessed by the significant body of watercolors and oils stemming from tours that took him throughout Europe, the Near East, and North America.

About 1907 he began to curtail his activity in commissioned portraiture in favor of work that gave him greater personal pleasure and to devote more time to his mural commissions. The 1909 exhibition of eighty-six of his watercolors at M. Knoedler Galleries in New York and the Brooklyn Museum’s purchase of eighty-three of these focused American attention on that aspect of his art.

Sargent worked as an official war artist for Britain during World War I. “Gassed” (1918-19; Imperial War Museum, London) is a monumental canvas documenting the events he witnessed close to the battle lines in France. Shortly after his death from degenerative heart disease, Sargent was honored with large memorial exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and at the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

“Study of Mrs. Hugh Hammersley”, 1892

Oil on canvas, 33 x 20 3/4 in. (84.1 x 52.7 cm)

Signed and inscribed (lower right): To Henry Tonks / John S. Sargent

Charles and Elizabeth Buchanan Collection (1989.41)

This study relates to the full-length “Mrs. Hugh Hammersley” (private collection, on loan to the Brooklyn Museum of Art) that was displayed at London’s New Gallery in 1893. That portrait, together with “Lady Agnew”, which was shown at the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition the same year, established Sargent as one of British society’s preeminent portraitists.

In 1891 London banker Hugh Hammersley had asked Sargent to paint a portrait of his vivacious wife, Mary Frances, née Grant (ca. 1863-1902), whom he had married in 1888. It was not until the following year, however, that work actually commenced, with sittings at the artist’s Tite Street studio throughout May and June.(1)1 Although theirs was a cordial relationship that lasted until Mary Hammersley’s death, the sittings were not without tension. Sargent’s biographer, Evan Charteris, cites a letter from the artist to the American expatriate artist Edwin Austin Abbey in which Sargent complained, “I have begun the routine of portrait painting with anxious relatives hanging on my brush . . . Mrs. Hammersley has a mother.” (2) 2

The study shows Mary Hammersley wearing the same rose magenta velvet “draped princess” gown and seated on the same Louis XVI sofa featured in the finished portrait.(3)3 While both works portray the wealthy young matron as personable, energetic, and direct, the study is far more intimate. Seen from above at close proximity, the figure is cropped and occupies a flattened compressed space, creating an overall effect of relaxed spontaneity. The fleeting nature of the captured moment is reiterated in the assured bravura brushwork that suggests, rather than delineates, form.

As the inscription indicates, Sargent gave the study to English painter Henry Tonks(4). Tonks had practiced medicine but turned to a full-time career as an artist in 1892, when he joined the faculty of the Slade School of Art in London. He frequented the informal Sunday gatherings held by Mrs. Hammersley in her Hampstead home, and it is likely that Sargent gave him the study as a souvenir commemorating their mutual friendship with the sitter as well as Tonks’s decision to quit medicine, made at the time the portrait was underway.

In addition to its obvious importance in relation to the finished work, the study has long held the reputation as one of the most successful demonstrations of the artist’s ability to create an image that expresses likeness and personality without sacrificing artistry.

BDG

Bibliography:

Evan Charteris, “John Sargent” (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927); William Howe Downes, “John S. Sargent: His Life and Work” (Boston: Little, Brown, 1927); Richard Ormond, “John Singer Sargent: Paintings, Drawings and Watercolors” (New York: Harper and Row, 1970) Carter Ratcliff, “John Singer Sargent” (New York: Abbeville Press, 1982); Marc Simpson, “Uncanny Spectacle: The Public Career of the Young John Singer Sargent”, exhib. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press; Williamstown, Mass.: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1997).

NOTES:

1. The formal portrait and the study are dated variously in the Sargent literature as 1892, 1892-93, and 1893. Based on notations dated March 30, 1893, by Mary Hammersley documenting the commission (private collection), the correct date for the formal portrait is 1892. The study was doubtless painted during the same May-June 1892 sittings she recorded in connection with the large portrait.

2. Quoted in Charteris, “John Sargent”, p. 137.

3. A newspaper clipping annotated “Standard 1 May” contained in Mary Hammersley’s 1893 scrapbook (private collection) refers to the style as “draped princess.”

4. Sargent and Tonks probably began their long friendship in 1890. On Tonks, see Joseph Hone, “The Life of Henry Tonks” (London: W. Heinemann, [1939]).