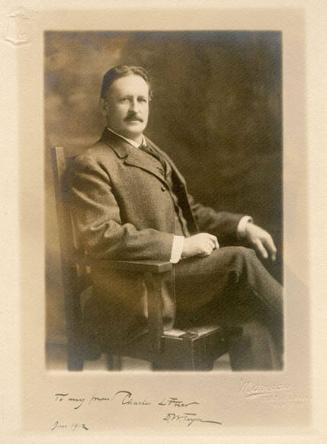

Gustave Adolph Hoffman

American, 1869 - 1945

Death-PlaceRockville, Connecticut

Birth-PlacePhiladelphia, Pennsylvania

BiographyHoffman immigrated with his family to Rockville, Connecticut at age 3 and lived in Rockville until he died. He first studied with Charles Ethan Porter in Porter’s Hartford studio and remained very close to Porter, his neighbor in Rockville, for the rest of Porter’s life. He also studied in Paris and Munich. He was noticed early on in Germany for his etchings. He did show in Hartford occasionally, participating in the first exhibition of the Connecticut Academy of Fine Arts in 1910. He was also the subject of a long article in Hartford Courant on August 9, 1925, about his life and career. However, he never really became an active participant in any of the Hartford art organizations, apparently preferring to remain close to home in Rockville, painting portraits, making etchings, and later in his life, landscapes in oil. Gustave Adolph Hoffman was born January 28, 1869 in Cottbus, Brandenburg, Germany. His father, Theodore Hoffman, was the head designer of one of Germany’s largest woolen mills. His mother was Wilhelmine Gerbach Hoffman. The family immigrated to Rockville, Connecticut in 1870. Gustave was temporarily left behind but rejoined his parents in 1872. His father was a designer for the American Mills in Rockville. Some of his designs were included in the Philadelphia Exposition in 1876. The family lived at 5 Laurel Street, which would remain Hoffman’s home for the rest of his life.

Around 1883, just three months before Hoffman was to graduate from grammar school, he was forced to leave school to go to work in the Samuel Fitch Cotton Mills to help support the family. He was initially paid 50 cents for a 12-hour day with only an hour off for lunch. An article in the Hartford Courant published in 1925 said: “Then as now, he was small and high strung and not very strong. When he worked, he worked on his nerves, rather than on his muscles, with the result that he worked far beyond his nervous force, leaving him a prey to the inroads of the bronchial and nervous trouble which have since been the nemesis of his life.” After a year at the Fitch mills he went to work in Brigham Payne’s Button Shop. His pay increased to $1.05 a day. However, the shop closed after 6 months and he went to work in Cyrus White’s Stone Mill where his pay reverted to 50 cents a day. He then worked in a dry goods store selling cotton materials. “As a boy, romantic and lonely, he stole away to his roof or to the shade of a tree to put on paper the pictures that formed in his head…People in Rockville still remember those wonderful elephants and ships he used to draw.” (Hartford Courant, August 9, 1925). Around 1885 his father died. He had been severely disappointed in his own artistic career and strongly opposed such a career for his son. However, after his father’s death his mother was more supportive of his artistic talents. The Courant article included an imaginary conversation between young Hoffman and his mother, probably drawn from Hoffman’s memories and diaries.

“Gussie,” she said fondly, “I want you to be something. I want you to study. I want you to have a chance before it is too late. I don’t know how we’ll do it, but it will be done.” Now what would you like to be?”. “A watchmaker,” said the boy, thinking only of pleasing her the most. “Anything else?” “An engraver, “ he answered to please his brother Paul who wished him to be a bank note engraver. “Now isn’t there something else you’d like to be?” she pressed him further. “Yes mother,” said Hoffman earnestly, “An Artist.”

However, the family desperately needed the income so Hoffman continue to work at the dry goods store of William Thompson, who would later found the Brown Thompson department store in Hartford. He worked from 7 to 10 with two hours off during the day.

Around this time Hoffman began taking lessons from Charles Ethan Porter who also lived in Rockville. Hoffman was 17 and Porter was 38 or 39. Porter had recently returned from studying in Paris and was at the height of his creativity. Hoffman initially took six lessons in Porter’s Brown Thompson Building studio in downtown Hartford. The lessons were paid for by Hoffman’s brother Paul, who was a court stenographer. Paul remained Hoffman’s chief sponsor throughout most of his career. Hoffman was devoted to Porter until Porter’s death in 1923. Toward the end of Porter’s life, Hoffman and his sister were almost Porter’s only friends.

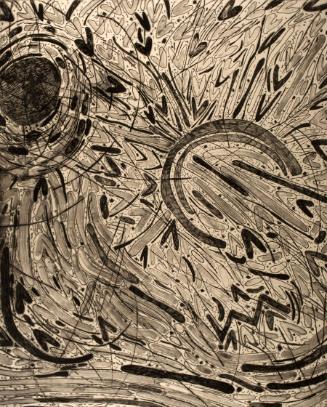

While working in the mills, or dry goods stores, Hoffman would always draw in his spare time. At Porter’s suggestion, in 1888 at the age of 19, he attended the National Academy of Design in New York City and lived with his brother Paul on East 31st Street. Before then Hoffman had never been further away from Rockville than Hartford. Hoffman remained studying in New York City for three years where he concentrated on portrait painting. Again at Porter’s suggestion, he then studied in Paris. In 1889 he moved back to Rockville, but in September 1891 he attended the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, still supported by his brother Paul. In Munich Hoffman studied painting with Carl Marr, and etching with Samuel I. Wemban. He also studied the harpzither with Wemban’s wife. Hoffman’s etchings were well received in Germany. In 1893 he was elected to the Munich Society of Etchers and exhibited his etchings by invitation at the Glass Palace in Munich. He returned to New York City in 1894 and took a studio in the same building as Porter.

In October 1894 he returned to Rockville and established a studio in the Maxwell Block on Main Street, a short walk from his home on Laurel Street. Porter also returned to Rockville. Hoffman would often visit Porter in his house on Spruce Street and his studio at the top of Fox Hill, just around the corner from Hoffman’s house. He also often travelled with Porter on painting excursions.

In 1895 Hoffman exhibited some etching plates at the National Academy, which received notice in the New York Times. “There are some plates by an etcher named Hoffman, who deals admirable with both figures and landscapes. We would like to place him with the Americans, but he appears to hail from the other side.” Hoffman was pleased with the notice by said: “True I was born in Germany and studied in Germany, but I want to be known as an American painter of American life.”

“In the early 1890’s Porter had grown close to two young white Connecticut Artists: Samuel Morley Comstock (1870-1900) of Essex and Gustav (sic) Hoffman of Rockville. Comstock and Porter toured galleries and had dinner together in New York, visited one another in Rockville and Essex (where Comstock lived), and spent a couple of summers painting in Essex. They exhibited jointly in the Rude exhibitions in Springfield and at the Hartford YMCA until Comstock died of tuberculosis in 1900 at age twenty-nine.” (African American Connecticut explored, page 222)

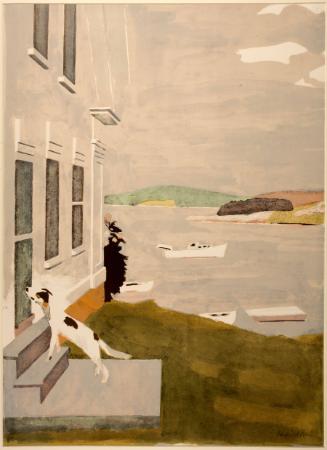

In the fall of 1896 Porter and Hoffman made a painting trip tour of New England. “He (Porter) and Hoffman tramped through New England, making studies of flowers, debating as they went the ’modernistic’ method of painting in complementary colors that Hoffman had taken up in Munich and that Porter rejected. They made autumnal painting expeditions to the Connecticut shore towns of Old Hamburg and Essex.” (Brown, Cummings, Fusscas page 104, from Hoffman’s Autobiography)

In 1898 Hoffman, Comstock, and Porter spend the summer in Essex and held a joint exhibition at George M. Bolton’s photography studio in Rockville.

Comstock died in early 1900. In 1901, Hoffman’s studio in Rockville burned, destroying his entire inventory of work. Around 1905, Hoffman’s fragile health declined from overwork, undoubtedly made worse by the death of his young friend and the destruction of his studio. Hoffman began to spend the winter in Florida and in 1910 made an extended voyage to Egypt, Naples, Rome, Venice, Florence, and Munich to regain his health.

He retuned to Rockville in 1911 establishing a studio in his home on Laurel Street. He was still primarily painting portraits and making etchings. He had invented a process for painting an etching in all colors at the same time rather than one at a time. Around this time he also began to paint landscapes in oil. The New York Sun noted: “etchings have been purchased by the Royal Gallery in Munich, the Art Museum at Frankfort, the National Gallery of Berlin and have been highly commended and accepted by Sir Sidney Colvin for the British Museum.”

“He has buried himself deep in the hills of Rockville with his sister, Miss Martha Hoffman, who shares his ideals and aspiration in art, and criticizes him when he fails to respond to them. “I am happy. I have succeeded in being Hoffman.”

In his diaries from this period, Hoffman often mentions visiting Porter in his home on Spruce Street or in his Fox Hill studio, either alone, or with his sister Martha. The Brown, Cummings, Fusscas book says, “some say that Martha was the love of Porter’s life”. It is more likely that he simply returned her kindness with friendly devotion. As Porter’s health and finances declined, Hoffman often accompanied him going door to door in Rockville and the neighboring towns trying to sell Porter’s paintings.

Hoffman’s mother died in 1920 leaving Hoffman and his sister alone in the Laurel Street house. On March 6, 1923, Porter died.

In spite of these personal tragedies, Hoffman’s career was thriving. He was often invited to lecture in the towns around Hartford and was the subject of long laudatory features in the Hartford Courant in 1923 and 1925.

His sister Martha died in 1940. Hoffman’s own health had been declining for several years and his eyesight began to fail. On August 30, 1945 he died at his home in Rockville on the day MacArthur landed in Japan. He is buried in the Grove Hill Cemetery in Rockville. At the time of his death he was survived by two brothers, Theodore of Seattle and George of Los Angeles, and two sisters, Mrs. Fred B. Herman of Hartford, and Mrs. Frank P. Marshall of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

His personal papers, including his diaries, several paintings, and many etchings, are held by the Vernon Historical Society. In March of 1971 he received his first and only retrospective exhibition at the Vernon Historical Society. In 1983 Mrs. Ida Durand donated several of his works to the New Britain Museum of American Art. During his lifetime, Hoffman was far more successful and well known than his first teacher and mentor Porter. However Porter has experienced a major “rediscovery”, and his works are now widely sought after, while Hoffman is virtually unknown.

In 2013 a book entitled “The Colored Artist” by Ed Ifkovic of West Hartford was published. It is, according to Ifkovic, an entirely fictional account of the relationship between Porter and the “two young white Connecticut artists” Hoffman and Comstock. This fictional account posits that the young, wealthy, and beautiful Comstock was the center of a three-way relationship between the men. Comstock is shown as worldly and an active participant in the New York gay scene to which he introduces Porter and Hoffman. Porter, 20 years older, is quiet and withdrawn, while Hoffman is intrigued but hesitant. In the end, Comstock dies young of tuberculosis leaving both Hoffman and Porter devastated. Porter retreats into depression and alcoholism, while Hoffman struggles to understand his own unrealized feelings, attempting to keep his friend Porter afloat.

It is easy to understand a fascination with the relationships between these three painters, an older black man and his two young and talented friends, none of whom ever married.

© Gary W. Knoble

Brown, Barbara; Cummings, Helen; Fusscas, Helen; “Charles Ethan Porter 1847?-1923”, The Connecticut Gallery, 1986

Cummings, Hildegard “Charles Ethan Porter, African-American Master of Still Life”, NBMAA, 2007

Cummings, Hildegard “Charles Ethan Porter”, African American Connecticut Explored, 2013

Hartford Courant, 11/18/1898, 2/14/1916, 3/22/1923, 4/22/1923, “The American Artist Comes Home” 8/9/1925, 12/1/1940, Obituary 8/31/1945, 3/23/1971, 3/28/1971

Gustave Hoffman, “Autobiography”, manuscript

Hartford Black History Project, “Citizens of Color, 1863-1890: the Talented Tenth”

Merrill, Peter C., “German Immigrant Artists in American: A Biographical Dictionary”, 1997

Person Type(not assigned)