Image Not Available

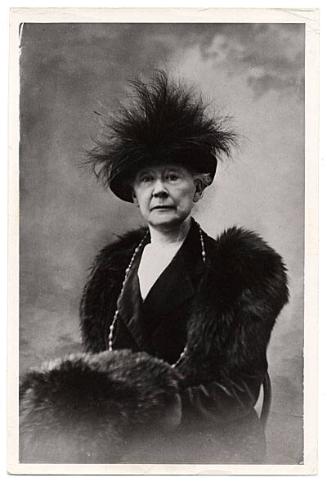

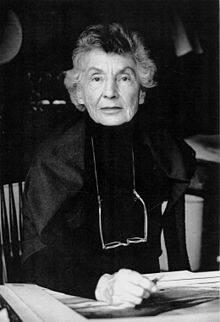

for Cecilia Beaux

Cecilia Beaux

1855 - 1942

After the war, Beaux began to spend some time in the household of "Willie" and Emily, both proficient musicians. Beaux learned to play the piano but preferred singing. The musical atmosphere later proved an advantage for her artistic ambitions. Beaux recalled, "They understood perfectly the spirit and necessities of an artist's life."[9] In her early teens, she had her first major exposure to art during visits with Willie to the nearby Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, one of America's foremost art schools and museums. Though fascinated by the narrative elements of some of the pictures, particularly the Biblical themes of the massive paintings of Benjamin West, at this point Beaux had no aspirations of becoming an artist.[10]

Her childhood was a sheltered though generally happy one. As a teen she already manifested the traits, as she described, of "both a realist and a perfectionist, pursued by an uncompromising passion for carrying through."[11] She attended the Misses Lyman School and was just an average student, though she did well in French and Natural History. However, she was unable to afford the extra fee for art lessons.[12] At age 16, Beaux began art lessons with a relative, Catharine Ann Drinker, an accomplished artist who had her own studio and a going clientele. Drinker became Beaux's role model, and she continued lessons with Drinker for a year. She then studied for two years with the painter Francis Adolf Van der Wielen, who offered lessons in perspective and drawing from casts during the time that the new Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts was under construction. Given the bias of the Victorian age, female students were denied direct study in anatomy and could not attend drawing classes with live models (who were often prostitutes) until a decade later.[13] t 18, Beaux was appointed drawing teacher at Miss Sanford's School, taking over Drinker's post. She also gave private art lessons, and produced decorative art and small portraits. Her own studies were mostly self-directed. Beaux received her first introduction to lithography doing copy work for Philadelphia printer Thomas Sinclair and she published her first work in St. Nicholas magazine in December 1873.[14] Beaux demonstrated accuracy and patience as a scientific illustrator, creating drawings of fossils for Edward Drinker Cope, for a multi-volume report sponsored by the U.S. Geological Survey. However, she did not find technical illustration suitable for a career (the extreme exactitude required gave her pains in the "solar plexus"). At this stage, she did not yet consider herself an artist.[15][16]

Beaux began attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1876, then under the dynamic influence of Thomas Eakins, whose great work The Gross Clinic had "horrified Philadelphia Exhibition-goers as a gory spectacle" at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876.[17] She steered clear of the controversial Eakins, though she much admired his work. His progressive teaching philosophy, focused on anatomy and live study (and allowed the female students to partake in segregated studios), eventually led to his firing as director of the Academy. She did not ally herself with Eakins' ardent student supporters, and later wrote, "A curious instinct of self-preservation kept me outside the magic circle."[18] Instead, she attended costume and portrait painting classes for three years taught by the ailing director Christian Schussele.[19]

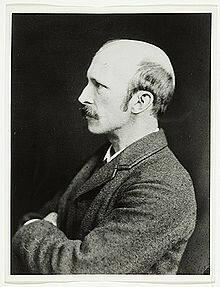

After leaving the Academy, the 24-year-old Beaux decided to try her hand at porcelain painting and she enrolled in a course at the National Art Training School. She was well suited to the precise work but later wrote, "this was the lowest depth I ever reached in commercial art, and although it was a period when youth and romance were in their first attendance on me, I remember it with gloom and record it with shame."[20] She studied privately with William Sartain, a friend of Eakins and a New York artist invited to Philadelphia to teach a group of art students, starting in 1881. Though Beaux admired Eakins more and thought his painting skill superior to Sartain's, she preferred the latter's gentle teaching style which promoted no particular aesthetic approach.[21] Unlike Eakins, however, Sartain believed in phrenology and Beaux adopted a lifelong belief that physical characteristics correlated with behaviors and traits.[21]

Beaux attended Sartain's classes for two years, then rented her own studio and shared it with a group of women artists who hired a live model and continued without an instructor. After the group disbanded, Beaux set in earnest to prove her artistic abilities. She painted a large canvas in 1884, Les Derniers Jours d'Enfance, a portrait of her sister and nephew whose composition and style revealed a debt to James McNeill Whistler and whose subject matter was akin to Mary Cassatt's mother-and-child paintings.[22] It was awarded a prize for the best painting by a female artist at the Academy, and further exhibited in Philadelphia and New York. Following that seminal painting, she painted over 50 portraits in the next three years with the zeal of a committed professional artist. Her invitation to serve as a juror on the hanging committee of the Academy confirmed her acceptance amongst her peers.[23] In the mid-1880s, she was receiving commissions from notable Philadelphians and earning $500 per portrait, comparable to what Eakins commanded.[24] When her friend Margaret Bush-Brown insisted that Les Derniers was good enough to be exhibited at the famed Paris Salon, Beaux relented and sent the painting abroad in the care of her friend, who managed to get the painting into the exhibition.[24] Cecilia Beaux died at Green Alley at the age of eighty-seven, and was buried in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. In her will she devised that a Duncan Phyfe rosewood secretaire made for her father go to her cherished nephew Cecil Kent Drinker, a Harvard physician, whom she had painted as a young boy.[48][49]

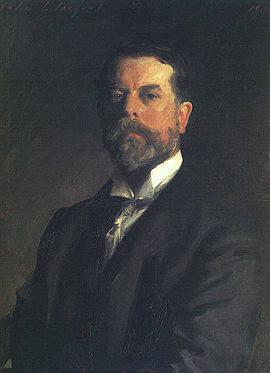

Though Beaux was an individualist, comparisons to Sargent would prove inevitable, and often favorable. Her strong technique, her perceptive reading of her subjects, and her ability to flatter without falsifying, were traits similar to his. "The critics are very enthusiastic. (Bernard) Berenson, Mrs. Coates tells me, stood in front of the portraits – Miss Beaux's three – and wagged his head. 'Ah, yes, I see!' Some Sargents. The ordinary ones are signed John Sargent, the best are signed Cecilia Beaux, which is, of course, nonsense in more ways than one, but it is part of the generous chorus of praise."[50] Though overshadowed by Mary Cassatt and relatively unknown to museum-goers today, Beaux's craftsmanship and extraordinary output were highly regarded in her time. While presenting the Carnegie Institute's Gold Medal to Beaux in 1899, William Merritt Chase stated "Miss Beaux is not only the greatest living woman painter, but the best that has ever lived. Miss Beaux has done away entirely with sex [gender] in art. During her long productive life as an artist, she maintained her personal aesthetic and high standards against all distractions and countervailing forces. She constantly struggled for perfection, "A perfect technique in anything," she stated in an interview, "means that there has been no break in continuity between the conception and the act of performance." She summed up her driving work ethic, "I can say this: When I attempt anything, I have a passionate determination to overcome every obstacle…And I do my own work with a refusal to accept defeat that might almost be called painful."[52]

REFERENCES:

Beaux, Cecilia. Background with Figures: Autobiography of Cecilia Beaux. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1930.

Goodyear, Jr., Frank H., and others., Cecilia Beaux: Portrait of an Artist. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1974. Library of Congress Catalog No. 74-84248

Tappert, Tara Leigh, Cecilia Beaux and the Art of Portraiture. Smithsonian Institution, 1995. ISBN 1-56098-658-1

Public Domain This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

Person Type(not assigned)

Terms