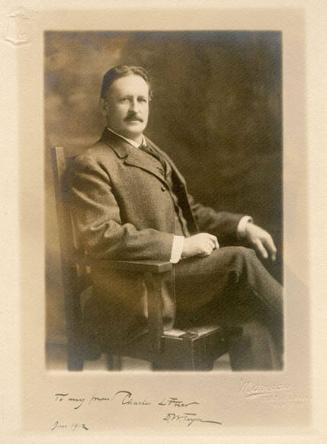

Charles Foster

1850 - 1931

(A Hartford Biography)

© Gary W. Knoble 2014

Charles B. Foster, whom James Britton dubbed “The Man from Maine” was a quiet man, a quiet painter, and lived a quiet life as a life long bachelor in rural Farmington, Connecticut. He loved to paint the “soft” landscapes around his studio that was located in a barn just up the road from the home of his long time friend Robert Bolling Brandegee.

Foster was born on July 4, 1850 in North Anson Maine. He was a younger brother of the famous tonalist painter, Ben Foster.

In the early 1870’s he went to Paris to study where he joined a group of painters including the Hartford artists Montague and Charles Noel Flagg, Robert Bolling Brandegee, William Bailey Faxon, and their New Haven friend John Henry Niemeyer. He studied first with Alexandre Cabanal at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and later with Louis Jacquesson de la Chevreuse (a student of Ingres). James Britton, who later was one of Foster’s students at Flagg’s Connecticut League of Art Students in Hartford, wrote in the Hartford Courant on February 7, 1911:

“Mr. Brandegee told me recently that it was Professor John Niemeyer of New Haven that recommended the school of Chevreuse (Jacquesson – student of Ingres) in Paris to the Connecticut men. (Neimeyer, Brandegee, Montague and Charles Noel Flagg, Foster and Faxon) So it happened that while Hunt in Boston taught upon the ideas of Conture (Thomas) and color, the strong men of Connecticut held fast to Ingres and the line-and incidentally struck color in original variety.”

Upon his return from Paris, Foster followed Brandegee to Farmington, Connecticut where he lived for the rest of his life. There, he was part of an art colony that formed around Brandegee that included, from time to time, the Flaggs, William Gedney Bunce, Alan Butler Talcott, and Walter Griffin.

Foster loved to paint the “soft” landscapes around Farmington. He lovingly described this landscape in an article he wrote in 1901 for the Farmington Magazine entitled, “A Glance at the Farmington Landscape”.

“’Such a thoughtful idea of Providence, to run rivers through all large cities,’ said the lady. If she has ever been in Farmington she would have considered the north and south plan equally felicitous. This arrangement brings effects of light and shadow at morning and evening hours that an east and west valley does not. It also allows the summer south breeze full play through it – a satisfactory arrangement, as we all know, - while no such sweep is allowed the west winds of winter. What a beautiful, distinguished valley it is, hills and meadows doing just the right thing. Beyond the warm gray lichen-flecked post and rail fence, suggesting bars of music, as the hilltop hay field and old fashioned apple orchard, sloping away to a pasture where the cows in the summer hazes look almost like masses of wild flowers, their color is so soft and delicate. Then come the steeper open fields gliding down to the main street now hidden by fine old trees. Here and there shows a bit of roof or old red barn, and charm of all, the most exquisitely proportioned church spire ever designed. Still further appear the delicious meadows, with the river and its offspring, the ‘Pequabuc’ winding about just as fancy takes them, as though delaying as long as possible the moment when they are to be swallowed up by the swallower of all rivers. (I remember quite well the shock produced by suddenly realizing that is was not the same water which ran through my favorite brook year after year, and taking what comfort I could from the constancy of the banks and rocks.) The meadows are frequently dotted with white, again pink or red at sunset. Then begins the western slope through a wood, more pastures, and finally the dark wooded hills touching the sky in a line as beautiful and elegant as a perfect arm, wrist and hand, far pleasanter for every day comradeship than bold arrogant outlines. May our valley be always preserved from the landscape “gardener”, an unaccountable mania that so many of us have for making nature suggest furniture.”

Foster’s studio was in a barn at the rear of 42 Mountain Road. Foster and his studio are colorfully described in an entry James Britton wrote in his diary in August of 1927, recalling his student days.

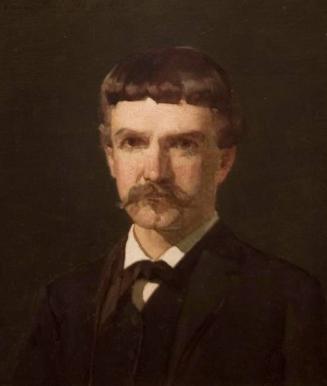

“Foster was a fastidious old womanish kind of person, who had a way of talking to us when we were students rather patronizingly. He treated us a little as though we were hopeless imbeciles and his slight pose made us rather tired. His position of admitted inferiority as an artist to Brandegee who’s studio was a little way down the hill, kept him within bounds however, as he was with us heartily in admiration of Brandegee. But I can see Foster now submitting to our visits, which usually took him unawares and which he could hardly avoid as in the summer time his studio door was usually open. I can see him sitting in his rocking chair across the studio floor which was highly polished wood holding a cigarette very gently and puffing very lightly as he listened to our questions or our bits of news and often raised his head and turned it toward us with raised eyebrows to ask what it we were last saying. The idea was of course that our chatter was of such little consequence to him that he couldn’t be bothered hearing it although he had put himself in a position of listener. He was a little man and when he walked about the studio to put up his pictures for us to see, he used a measured stride which was intended to be as dignified as a little man could make it. It is a shame to take advantage of Foster, but his mild snobbery exercised during the years before I had reached a point where I could be of any use to him made me tired. His manner changed considerably after I began to write about the artists for the papers in Hartford and New York. Perhaps he was a little justified in snubbing us in the beginning as we went there first with Gernhardt principally to see the large portrait of Foster by Montague Flagg which he had hanging in the studio. This picture he gave to the Metropolitan Museum after M. Flagg died but as yet I have not seen it hung although the Museum made a photographic print of it for me. When Ben Foster died two years ago or so he left most of his property to Charlie and I imagine Ben was fairly well off. I must ask (C. V.) Mitchell to take me out to see Foster some day soon in his car. There were times in the old days in summer when the weather was very hot that Foster used to almost entirely forget his dignity. Then as we would sit out side on the ground around his studio and smoke, Foster used to burn grass at night as a “smudge” to keep away mosquitoes. McManus and Smith and I used to go often to Farmington in those days on Saturdays and Sundays.”

Foster taught for a time at the National Academy and at Flagg’s Connecticut Art Students League in Hartford. He was a founding member of the Connecticut Academy of Fine Arts in 1910.

A lifelong bachelor, Foster died on June 12, 1931, in Farmington.

A memorial exhibition of Foster’s works was held at the Wadsworth Atheneum in October of 1931. The catalogue contained several tributes to him. “Although thoroughly trained under the tradition on Ingres, Mr. Foster like his later brother, Ben Foster, painted principally landscapes, excelling in the treatment of skies, and from his studio he had every opportunity to study them, as well as the changing foliage of his beautiful surroundings.” Faxon, his friend and fellow student from the Paris days wrote, ‘Those who have had the pleasure of knowing Charles Foster, will, I am sure, treasure the memory of a true gentleman who was loyal and kindly, broad in his sympathies, modest, a searcher after the elusive truth which must be evident in his work shown in this Memorial Exhibition.’”

Harold Abbott Green, another of Foster’s students who’s portrait of Foster was included in the exhibition, asked James Britton to write an article on Foster and the memorial exhibition for the Hartford Courant. In preparation for the article, Britton visited the exhibition and noted it in his diary.

October 24, 1931

“Go up to the Museum by Prospect St. E (his brother Ern) leaving his car as he says ‘in someone’s backyard’ and we go in the museum through the Public Library side door. Find Foster’s paintings show in the small gallery VI. First glance turns up nothing exciting but as I move around I see the self portrait with the golf cap which seems to me altogether the shot of the show, much finer than Green’s portrait of F. which is more conventional & has too much red in it – background red & chair cushions red a sort of low toned red the face is yellow and the clothes brown but Foster’s self portrait is very good in color grey coat with a dark collar white collar ruddy face pinky grey cap background a very favorable note dark grayish blue and green but neutral. Likeness good in general but not in an intimate way. Modeling of flesh excellent placing and shape of ear right, line of neck shoulder & back all that could be desired of a difficult form. Make some notes from which to write an article for the ‘Courant’. See the El Greco ‘Crucifixion’ & a new Degas not much.” (Misc. Volume 11, page 48)

Britton’s article appeared in the Courant on October 28, 1931 and provides a fitting tribute to this quiet painter.

October 28, 1931, “Charles Foster: Mr. Britten Pens, Appreciation of the Landscape Painter. Letter to the Editor:

Adding to the achievement of living to be eighty-one years old, Charles Foster left behind him a number of creditable paintings. He, like many American artists, may have been content to contemplate a merely posthumous fame. At any rate, I never knew of his making much of an effort to promote celebrity for himself. He was content to be quiet and busy and alone with his work in the neat spacious studio that nestled on the mountainside in Farmington.

His seeking was for quiet. He cultivated quiet however possible. He spoke quietly, he moved quietly, he painted quietly, and to make certain of continued quiet at least in the domicile, he never married. He shunned excitement. The rattle of crickets bothered him, and the sudden plaint of a friendly cow would startle him: yet he would sit out in dangerous snake country and calmly smoke and paint and be silent.

We used to disturb him, several of us who were pupils of Charles Noel Flagg during years close to the turn of the century, seeking him for criticism of our early efforts. He was the available landscape specialist, and his comment was brief and pointed. Farmington was then a mecca of a sort, with Brandegee, Foster, and Walter Griffin at work there. Harry Gernhardt discovered the place as good sketching ground and called it ‘the American Barbizon’.

Foster had the ideal situation for a landscape painter. His studio clung to the mountain just below a magnificent grove of evergreens. Beyond the dark grove the point of Rattlesnake Hill gleamed in the sun. Many a picnic we had in that grove, Foster’s studio door was always open. One of the pictures he had there in those days I still remember. It showed the mountainside covered with frost, the effect of frost very cleverly managed.

In the Memorial Exhibition now open at the Morgan Memorial, the agreeable surprise is supplied by the ‘self-portrait’, which I have never seen until now. I couldn’t find a date on the canvas but I imagine it may have been painted twenty years ago or so. It represents the jaunty Charles Foster, the occasional holiday maker who would saunter forth carefully gotten up in a costume topped by a natty golf cap. Before I went away to live in New York I used to encounter in Hartford our friend of the ‘self-portrait’. I can see him now standing over near the old City Hall waiting for his Farmington trolley, gently tapping the pavement with his cane, lightly puffing a cigarette and making quiet remarks about the lines of the Bullfinch cupola. Here he is in the ‘self-portrait’ destined to live centuries beyond his mortal 81 years.

It is seldom that a confirmed landscape painter turns to portraiture with such success. I want to give the picture another title – ‘The New Englander’ or ‘the Man from Maine’ or ‘Off for the Afternoon’. The picture is gay with jauntiness. Foster in the rarest bonny mood.

The picture has a winning simplicity of plan, a subtle rhythm of design, a restraint in its color - and adequate harmony - grey coat, dark color, white collar and ruddy complexion. And the golf cap! I have yet to see, elsewhere a golf cap painted to distinction. For contrast, Mr. Harold Green’s portrait represents the philosophic Charles Foster, the man who once taught the rule of the Academy, the contemplative, studious, professorial Charles Foster who had dabbled in aesthetics and been rescued by the smell of paint, turpentine and tobacco. Green’s portrait gives evidence of the struggle. It reveals the stern line to the mouth of the man who stuck doggedly to the role of painter and to the solitary life.

Foster’s landscapes celebrate the natural beauty of Connecticut. In many of his canvases the color is high pitched and ripe as in good Pissarro’s. The picture of Farmington’s Main Street with the James Lewis Cowles house is an extremely fine piece of work. Foster’s preoccupation generally was with tonal subtleties. Here he selected a view of the fine old colonial house in which the tall columns were inconspicuous, and concentrated, not so much upon the doorway, as upon the forms and tonalities of the trunks of trees standing in slight relief against the weathered wall. As if to applaud himself for doing an unusually good job, he runs a slight riot in the foreground by putting down an almost vivid green.

All his life Foster practiced suppression in his art. In the many snow pictures you never find a glaring white. There is a very successful snow picture in the present exhibition, the one called ‘Toward Evening’, in which broad bands of grey pink cloud against a grey green sky hold the twilight above the graying whites of the snow. Nowhere are there sharp contrasts or strong accents. Everywhere there is subtlety. He paints a ‘Moonrise’ in which the relation between the moon and the sky is close, yet he manages to suggest new light in the moon, waning tight in the sky and the diffused illumination of the afterglow on the ground and in the trees.

Foster winced at the melodramatic. He would never paint the moon as a beacon popping out of a black sky. He concerned himself with refined situations. Not for him were pictorial orgies a la Vincent Van Gogh. He could admire the robustious Brandegee, his inspired neighbor, when he literally threw paint from a loaded palette with a knife, and spread it into shapes of harmless peonies, but for himself he held a check for all enthusiasms. A bit of a Puritan, trained in the Quartier Latin, drilled with the Roman dictum of Pere Ingres, Foster found a kind of artistic reincarnation in the Farmington hills. By dint of devotion to the great ‘out of doors’ he produced some real American works of art, rendering himself immortal in the character of ‘The New Englander’. ‘The Man From Maine’ the jaunty holiday maker off for the afternoon in a harmony of gray coat, dark collar, white collar, merry eye, and ruddy cheek. JAMES BRITTON, South Manchester, Oct. 25, 1931”

Three years later Britton’s wife Carol visited Farmington looking for a possible place for them to live.

January 17, 1934

“Weather good but grey. Carol mentions Farmington and I suggest it might be well to go out there and see if there is a place to have. ……….. Well here is the Farmington story near as I can remember C’s words. “Well, I passed Brandegee’s old place and it seemed to be quite fixed up, and I went up the hill to where Foster’s studio is and I saw some workmen over in a field opposite and they said Foster is dead and they didn’t think anyone had the studio. They were near a house, a fine looking place and they said it was Mrs. Riddle’s office. (Mrs. R was Miss Pope, richest woman in the town, an architect, and proprietor of a Boys School in Avon, also a survivor of the ‘Lusitania’ sinking, rescued by fishermen off the Irish coast. Her large country house sets away off across the estate to the north a completely isolated large wooden house built after the model of Washington’s Mount Vernon. As Miss Pope the lady was visited and some say courted by the English novelist Henry James. Miss Pope married Riddle and ex American Ambassador to Austria. The north end of her estate borders the highway to Hartford and has a fine looking gardener’s cottage there. At the south and where C says her ‘office’ is located is the hill road where stands the old Klauser house, and a little above Charlie Foster’s old plain barnlike studio, the chief architectural feature of which was a brick fireplace and a highly polished floor.) I asked C. about the studio and she went on. ‘Well there are two wooden houses in front of the studio toward the street and one of the families, Irish I think, keeps chickens in the studio.’ ‘For God’s sake’ I say ‘so that’s the way those darn people use that studio. Gives a pretty good idea of what they think of artists.’” (Misc. Volume 22, page 36)

Happily, the misused barn, which contained Foster’s studio, still stands in 2014.

Bentley, Edward P, “Biography of Charles Foster”, Ask/ART website, 2004

Britton, James, “Charles Foster”, The Hartford Courant, October 28, 1931

Foster,Charles, “A Glance at the Farmington Landscape” in Farmington, Connecticut, the Village of Beautiful Homes”, Farmington: Arthur Brandegee and Eddy Smith, 1906), page 6, (picture of his studio on Page 189)

Hartford Courant, 2/7/11, 10/20/31, 10/28/31

Leach, Charles, M.D., “Farmington Artists and Their Times – Giverny in Connecticut: part II”

“Memorial Exhibition of Paintings by Charles Foster at the Morgan Memorial, Hartford, Conn. October 19th to November 1st, 1931”, Wadsworth Atheneum, 1931

Person Type(not assigned)