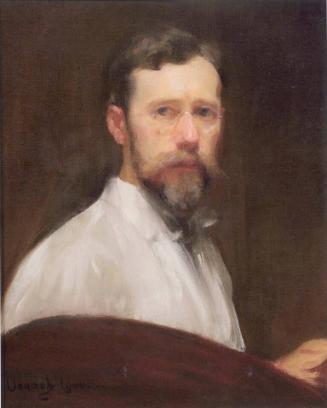

Abbott Handerson Thayer

American, 1849 - 1921

Birth-PlaceBoston, MA

Death-PlaceDublin, NH

BiographyAbbott H. Thayer was born in Boston, Massachusetts, but would call New Hampshire home for most of his life. At age 19, Thayer studied in New York City at the National Academy of Design, and later under Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) in Paris at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Thayer developed a distinctive style, after being heavily influenced by the Renaissance and Old Masters. The prominent use of natural elements, combined with his fascination with birds, led to his development of his own coloration theories. These theories transcended the camouflage techniques of birds, and would become an obsession for him once the United States was on the brink of World War I. Thayer became known as "the father of camouflage" after his death. His artwork inspired camouflage usage in World War II. EXTENDED BIO

Abbott Handerson Thayer (August 12, 1849 – May 29, 1921) was an American artist, naturalist and teacher. As a painter of portraits, figures, animals and landscapes, he enjoyed a certain prominence during his lifetime, and his paintings are represented in the major American art collections. He is perhaps best known for his 'angel' paintings, some of which use his children as models.

During the last third of his life, he worked together with his son, Gerald Handerson Thayer, on a major book about protective coloration in nature, titled Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom: An Exposition of the Laws of Disguise Through Color and Pattern; Being a Summary of Abbott H. Thayer’s Disclosures. First published by Macmillan in 1909, then reissued in 1918, it may have had an effect on military camouflage during World War I. However it was roundly mocked by Theodore Roosevelt and others for its biased assumption that all animal coloration is cryptic.[1]

Thayer also influenced American art through his efforts as a teacher, training apprentices in his New Hampshire studio. Thayer was born in Boston, Massachusetts. The son of a country doctor, he spent his childhood in rural New Hampshire, near Keene, at the foot of Mount Monadnock. In that rural setting, he became an amateur naturalist[2] (in his own words, he was “bird crazy”), a hunter and a trapper. Thayer studied Audubon's Birds of America on an almost daily basis, experimented with taxidermy, and made his first artworks: watercolor paintings of animals.

At the age of fifteen he was sent to the Chauncy Hall School in Boston, where he met Henry D. Morse, an amateur artist who painted animals. With guidance from Morse, Abbott developed and improved his painting skills, focusing on depictions of birds and other wildlife, and soon began painting animal portraits on commission.[3]

At age 18, he relocated to Brooklyn, New York, to study painting at the Brooklyn Art School and the National Academy of Design. studying under Lemuel Wilmarth.[3] He met many emerging and progressive artists during this period in New York, including his future wife, Kate Bloede and his close friend, Daniel Chester French. He showed work at the newly formed Society of American Artists, and continued refining his skills as an animal and landscape painter.[3] In 1875, after having married Kate Bloede, he moved to Paris, where he studied for four years at the École des Beaux-Arts, with Henri Lehmann and Jean-Léon Gérôme, and where his closest friend became the American artist George de Forest Brush. Returning to New York, he established his own portrait studio (which he shared with Daniel Chester French), became active in the Society of American Painters, and began to take in apprentices. Life became all but unbearable for Thayer and his wife during the early 1880s, when two of their small children died unexpectedly, just one year apart.[4] Emotionally devastated, they spent the next several years relocating from place to place. Although he was not yet secure financially, Thayer's growing reputation resulted in more portrait commissions than he could accept.[5] Among his sitters were Mark Twain and Henry James, but the subjects of many of his paintings were the three remaining Thayer children, Mary, Gerald and Gladys.

After her father died, Thayer’s wife lapsed into an irreversible melancholia, which led to her confinement in an asylum, the decline of her health, and her eventual death on May 3, 1891 from a lung infection. Soon after, Thayer married their long-time friend, Emma Beach, whose father owned The New York Sun. He and his second wife spent their remaining years in rural New Hampshire, living simply and working productively. In 1901, they settled permanently in Dublin, New Hampshire, where Thayer had grown up.

Monadnock in Winter, 1904, oil on canvas

Eccentric and opinionated, Thayer grew more so as he aged, and his family's manner of living reflected his strong beliefs: the Thayers typically slept outdoors year-round in order to enjoy the benefits of fresh air,[6] and the three children were never enrolled in a school.[7] The younger two, Gerald and Gladys, shared their father's enthusiasms, and became painters.[8] In 1898, Thayer visited St Ives, Cornwall and, with an introductory letter from C. Hart Merrian, the Chief of the US Biological Survey in Washington, D.C., applied to the lord of the Manor of St Ives and Treloyhan, Henry Arthur Mornington Wellesley, the 3rd Earl Cowley, for permission to collect specimens of birds from the cliffs at St Ives. During this latter part of his life, among Thayer’s neighbors was George de Forest Brush, with whom (when they were not quarreling) he collaborated on matters pertaining to camouflage. Thayer was resourceful in his teaching, which he saw as a useful, inseparable part of his own studio work. Among his devoted apprentices were Rockwell Kent, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Richard Meryman, Barry Faulkner (Thayer's cousin), Alexander and William James (the sons of Harvard philosopher William James), and Thayer's own son and daughter, Gerald and Gladys.

In a letter to Thomas Wilmer Dewing (c. 1917, in the collection of the Archives of American Art,[9] Smithsonian Institution), Thayer reveals that his method was to work on a new painting for only three days. If he worked longer on it, he said, he would either accomplish nothing or would ruin it. So on the fourth day, he would instead take a break, getting as far from the work as possible, but meanwhile instruct each student to make an exact copy of that three-day painting. Then, when he did return to his studio, he would (in his words) "pounce on a copy and give it a three-day shove again".[10] As a result, he would end up with alternate versions of the same painting, in substantially different finished states. By his own admission, Thayer often suffered from a condition that is now known as bipolar disorder. In his letters, he described it as “the Abbott pendulum,” by which his emotions alternated between the two extremes of (in his words) “all-wellity” and “sick disgust.” This condition apparently worsened as the controversy grew about his camouflage findings, most notably when they were denounced by former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. As he aged, he suffered increasingly from panic attacks (which he termed “fright-fits”), nervous exhaustion, and suicidal thoughts, so much so that he was no longer allowed to go out in his boat alone on Dublin Pond.

At age 71, Thayer was disabled by a series of strokes, and died quietly at home on May 29, 1921. In October 2008, a documentary film about Thayer’s life and work premiered at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Titled Invisible: Abbott Thayer and the Art of Camouflage, it featured a wide selection of his drawings and paintings, archival photographs, historic documents, and interviews with humorist P. J. O'Rourke, Richard Meryman, Jr. (whose father was Thayer’s student), camouflage scholar Roy R. Behrens, Smithsonian curator Richard Murray, Thayer’s friends and relatives, and others.

REFERENCES

Roosevelt, Theodore (1911). "Revealing and concealing coloration in birds and mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 30 (Article 8): 119–231.

Jump up ^ Ross Anderson, Abbott Handerson Thayer p. 12. (Everson Museum, 1982). OCLC 8857434

^ Jump up to: a b c "A Finding Aid to the Abbott Handerson Thayer and Thayer Family Papers, 1851-1999 (bulk 1881-1950), in the Archives of American Art". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

Jump up ^ Anderson 1982, p. 16.

Jump up ^ Anderson 1982, p. 19.

Jump up ^ Anderson 1982, p. 28.

Jump up ^ Anderson 1982, p. 20.

Jump up ^ Anderson 1982, pp. 31–32.

Jump up ^ Archives of American Art

Jump up ^ Anderson 1982, p. 27.

Jump up ^ Behrens, Roy (27 February 2009). "Revisiting Abbott Thayer: non-scientific reflections about camouflage in art, war and zoology". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B (Royal Society Publishing) 364 (1516): 497–501. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0250. PMC 2674083. PMID 19000975. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

Person Type(not assigned)