Image Not Available

for Asher Brown Durand

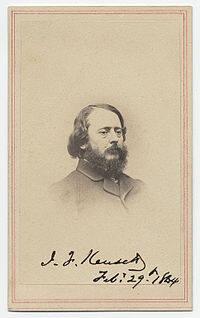

Asher Brown Durand

American, 1796 - 1886

Death-PlaceJefferson Village, NJ

Birth-PlaceJefferson Village, NJ

BiographyAsher Brown Durand (1796-1886)Asher B. Durand is best known as a first-generation Hudson River School painter, a place in the annals of American art that he shares with Thomas Cole, considered the father of the movement. Before turning to landscape painting, Durand pursued a successful career as an engraver. As he first became involved with painting, he worked with a number of subjects other than landscape, including portraiture, genre, and mythological, biblical, and literary themes. Even his landscape oeuvre is varied. Certainly inspired in great part by Cole, Durand experimented with allegorical, historical, and literary landscape compositions, considered in many quarters, at least until mid-century, aesthetically superior to pure landscape views. In a completely different vein, he executed pioneering plein-air studies in oil; he was probably the first American landscapist to engage in this practice. The variety of Durand’s output notwithstanding, his reputation is primarily based on his lovingly naturalistic, carefully detailed, and highly finished landscape views, which are considered exemplary of the Hudson River School style.

Durand was born and raised on a farm in Jefferson Village (later Maplewood), New Jersey. As a boy he was called upon to help his father, a sort of universal mechanic who augmented the family income with watch making and metalwork; his potential as an engraver was recognized at an early age. Following an apprenticeship with the Newark engraver Peter Maverick from 1812 to 1817, Durand became a partner, taking charge of the branch of the Maverick firm.

In 1820 John Trumbull, also in New York at the time, recognized Durand’s superior abilities as an engraver and asked him to reproduce his “Declaration of Independence”, prompting Maverick to dissolve the partnership. Upon completion of the work in 1823, Durand’s stature as an independent engraver was assured. He worked as an engraver until 1835, executing illustrations for gift books and annuals, countless banknote designs, and numerous portraits of clergymen, statesmen, and other notables. Attesting to his success, he was able to build a house for himself and his family in New York in 1827. He had married Lucy Baldwin of Bloomfield, New Jersey, in 1821, and by 1827 they had three children. The eldest, John, would be his father’s biographer.

Durand’s activity in the New York art world was impressive. In late 1825 he was instrumental in organizing the New York Drawing Association, which was renamed the National Academy of Design the following year. He subsequently served as the institution's recording and corresponding secretary, vice-president, and president (1845-61). He was also among the founders of the Sketch Club, later the Century Association.

Durand curtailed his engraving activity in the early 1830s; it is no coincidence that at this time his exhibits at the National Academy included engravings after his own designs as well as portraits in oil. In 1834 Luman Reed, notable for his generous patronage of American artists, among them Cole, supported Durand’s aspirations as a painter with commissions for several portraits as well as a literary and a genre scene. Durand’s career as a painter was launched. While the late 1820s and the early 1830s were witness to his continuing success in his first profession as a new one opened before him, these years also brought tragedy: after losing his firstborn daughter to illness in 1826, his wife passed away in 1830. She had given birth to their fourth child in 1829.

In 1837 Durand and his new wife, Mary Frank, whom he married in 1834 and with whom he would have two more children, joined the Coles on an excursion to Schroon Lake in the Adirondacks. The experience figured in Durand’s decision to become a landscape painter. The following year he exhibited nine landscapes at the National Academy. In 1840 Jonathan Sturges, business partner and son-in-law to Luman Reed, who had died in 1836, loaned Durand the money to travel abroad to sketch the scenery and see the sites but most important to get acquainted with the work of European artists, especially the Old Masters. Durand sailed in June 1840 with three artist friends John Casilaer, John F. Kensett, and Thomas Rossiter. His tour included London and other places in England, the Netherlands, Paris, Germany, Switzerland, and Northern Italy on his way to Rome. After wintering in Rome, where he set up a studio, he retraced his steps to England and returned to New York the following summer.

Durand, by now an indefatigable traveler, explored the Hudson River Valley in 1838 and toured a good deal of New England with Cole the following year. Indeed, until 1877, when, at the age of eighty-one he made his last trip to the Adirondacks, he went off virtually every season to sketch and paint in various locales. He visited the Adirondacks the most often and repeatedly toured the Hudson River and Catskill regions as well as Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. These trips yielded a steady production of Hudson River School landscapes as well as plein-air studies that he regularly exhibited at the National Academy and elsewhere to a receptive public, press, and circle of collectors.

In 1869 Durand, now a widower for the second time, returned to New Jersey and built a house on family property in Maplewood. It was there that he spent his remaining years, painting and exhibiting into the 1870s and, as long as health and age permitted, making his sketching excursions. His friends and colleagues in New York hardly forgot him, and in a memorable expression of their esteem a congregation of some twenty of them and their wives honored him with a surprise visit in June 1872, bringing food, drink, and conviviality. The occasion was a fitting testament to Durand’s leadership of the Hudson River School, a position he assumed after Cole's death in 1848, to his years of service to the National Academy, to his active participation in the New York art world, and most important, to his tireless devotion to landscape painting.

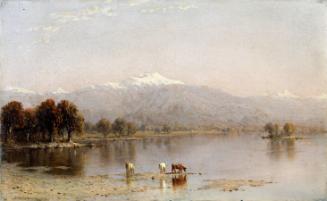

Sunday Morning, 1860

Oil on canvas, 28 1/8 x 42 1/8 in. (71.4 x 107 cm)

Signed and dated (lower center, on ledge): A B Durand / 1860

Charles F. Smith Fund (1963.4)

“Sunday Morning” was commissioned by the important Baltimore collector William T. Walters, who generously permitted Durand to exhibit the painting before he had even seen it.(1) The debut showing of Sunday Morning at the 1860 National Academy annual elicited general approbation in the press. One writer found “infinite satisfaction” in the work: “One is inevitably carried back to the experience of childhood, when the Sabbath was a day of delicious quiet. There is the same picturesque bridge that spanned the gurgling stream, the meeting-house crowns the summit of the gentle hill, the plough is left in the furrow, the sheep have sought in the shade protection from a summer sun.”(2)

Almost invariably, Durand chose a pastoral mode for his landscapes; he had a penchant for painting sunlit, verdant summer climes. He voiced this preference while addressing the “prejudice against green pictures”: I "cannot persuade” myself, he wrote, that “the sunny green of summer . . . is not beautiful, being, as it is, the first witness of organic life in the creation, the universal sign of unimpeded and healthy action; and, above all, the chosen color of creative Love for the earth’s chief decoration.”(3) How suitable an environment, one might at first conclude, for the distant hilltop church and the members of its congregation walking to Sunday services, passing a cross along the way.

Widespread at the time, of course, was the conviction that nature, “apart from its wondrous structure and functions that minister to our well-being,” was “fraught with lessons of high and holy meaning.”(4) Even more pointed, with respect to “Sunday Morning”, is Durand’s often quoted remarks on his habit of passing the Sabbath in communion with nature rather than attending church indoors.(5) While the New Britain picture offers both experiences to the viewer, it is largely given over to the lush, verdant environs of the church, which are laid out for the viewer’s spiritual delectation. One can only imagine the worship service about to begin moreover, at a great distance. The churchgoers, in turn, seem distant from the natural setting of which the viewer is so much a part, an aspect noted by a contemporary critic.(6)

Durand took care to embellish his scene with imagery associated with a state of quiet reverence. In the right foreground a plow sits in a furrow and six sheep rest from their grazing. The river in the middle distance is mirror smooth. Indeed, the sheep lying down in their hillside pasture and the stilled water surface effectively evoke Psalm 23 “ The Lord is My Shepard”. Durand’s friend and fellow artist Daniel Huntington put it well when he characterized “Sunday Morning” as “a poem, suggesting to the mind that stillness and feeling of sacred rest which is often experienced on a calm Sunday morning in a beautiful country.”(7)

Among Durand’s located works, two other paintings portray the theme taken up in “Sunday Morning”, interpolating the “lessons of high and holy meaning” in nature with those taught in church. A more domesticated but equally verdant locale serves as a setting for an earlier “Sunday Morning” (1839; New-York Historical Society), which, like the New Britain version, depicts worshipers on a country road leading to a church tucked amidst trees in the middle distance. A more mature and thoughtful variation on the theme can be found in the arched, vertical composition “Early Morning at Cold Spring” (1850; Montclair Art Museum, N.J.). This work, referred to as “Sabbath Bells” in the nineteenth century, was accompanied in the exhibition pamphlet by a poem by William Cullen Bryant when it was shown in 1850 at the National Academy: “O’er the clear still water swells / The music of Sabbath bells.”(8) Here, a lone gentleman silhouetted against a high-keyed water surface contemplates a church in the middle distance, once again nestled among trees in full summer foliage. Minuscule figures walk to Sunday worship, while our thoughtful gentleman stands in the embrace of a foreground coulisse of trees, a construct Durand frequently used that can suggest a natural “cathedral," especially in an upright, arched composition. These trees provide an aperture through which the viewer takes in the scene.

The New Britain “Sunday Morning”, though employing a horizontal format, also features an enframing aperture, formed by coulisse arrangements of land forms, trees, plants, shrubbery, and rocks at the far left and right. It is one of the few “aperture compositions” in a horizontal format in Durand’s oeuvre.(9) Overall, “Sunday Morning” is cast in the pastoral mode Durand so favored. It is enriched with the earthy irregularity of the picturesque, especially in the foreground. A vaguely classicizing, or Claudian, layout opens up beyond the foreground imagery. Typical are the formulaic steps back into space classically contained at the left and right by those coulisse constructs and in the middle and far distance by the bridge, the shadowy riverbank, the hills, and horizon line beyond.

Even before his trip abroad, Durand, instructed by prints, had begun experimenting with a type of landscape handed down to later generations by the seventeenth-century French landscapist Claude Lorrain, though he did not have an opportunity to study Claude firsthand until he arrived in Europe.(10) There, he also was able to see the work of John Constable, J. M. W. Turner, and the work of other English landscape painters at a time when the aesthetics of the Sublime, the Beautiful, and the Picturesque were still observed. The pastoral landscape was a mode that aestheticians had traditionally classified as Beautiful. More often than not, Durand embellished it with picturesqueness and frequently structured it within a loosely translated Claudian framework, creating, then, an amalgam drawn from various precedents, an amalgam represented in the New Britain “Sunday Morning”.

Despite the Englishness of the bridge and of the Gothic-style country church, “Sunday Morning” was described by the artist's son as “an ideal of American scenery.”(11) Gothic Revival architecture had been popular in America beginning in the 1840s and even churches in rural areas were built in the style. Then, too, perhaps Durand was recalling a hamlet he had sketched during a stop in England. The scenery in “Sunday Morning” is, indeed, too generalized to permit the identification of a specific site. As a reviewer noted in 1860, “The traveler who has resided in the Old World, and studied the rocks and trees of the New, will perceive in this agreeable picture a little English, Italian, and American scenery tastefully combined.”(12) Indeed, Durand rarely specified sites in his titles or in information accompanying exhibitions.(13)

“Sunday Morning” was not only well received by the press but was also included D. O. C. Townley's list of sixteen Durand paintings that “attracted the most attention” when they were exhibited and for which the artist “received the highest prices.”(14) Durand's son John considered “Sunday Morning” the culmination of his father’s ability.(15) As Jonathan Sturges wrote to Durand, ”We have no other artist who could paint it.”(16)

MBW

Bibliography:

Asher B. Durand Papers, New York Public Library; A. B. Durand, “Letters on Landscape Painting: Letter 1,” Crayon 1 (January 3, 1855): 1-2; "Letter 2,” Crayon 1 (January 17, 1855): 34-35; "Letter 3,” Crayon 1 (January 31, 1855): 66-67; “Letter 4,” “Crayon” 1 (February 14, 1855): 97-98; “Letter 5,” “Crayon” 1 (March 7, 1855): 145-146; “Letter 6,” “Crayon” 1 (April 4, 1855): 209-211; “Letter 7,” “Crayon” 1 (May 2, 1855): 273-275; “Letter 8,” Crayon 1 (June 6, 1855): 354-355; “Letter 9,” “Crayon” 2 (July 11, 1855): 16-17; John Durand, “The Life and Times of A. B. Durand” (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1894; reprint, New York: Kennedy Graphics, 1970); David B. Lawall, “A. B. Durand”, 1796-1886, exhib. cat. (Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum, 1971); David B. Lawall, “Asher Brown Durand: His Art and Art Theory in Relation to His Times” (New York and London: Garland, 1977); David B. Lawall, “Asher B. Durand: A Documentary Catalogue of the Narrative and Landscape Paintings” (New York and London: Garland, 1978

. Lawall, Documentary Catalogue, p. 127.

. "Academy of Design Exhibition: Third Notice," Evening Post, May 26, 1860, p. 1.

. Durand, “Letter 6,” p. 210.

. Durand, "Letter 2,” p. 34.

. Durand, Life and Times, pp. 145-46.

. The writer observed that those on their way to worship seem shut out from the scene of beauty around them ("Academy of Design Exhibition. Third Notice," p. 1).

. Daniel Huntington, Asher B. Durand: A Memorial Address (New York: Century Association, 1887), pp. 36-37.

. See B[arbara] D. G[allati], “Early Morning at Cold Spring,” in John Howat et al., American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, exhib. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), p. 111.

. The only other example among his located works that resembles the New Britain picture is a canvas known only as Landscape (private collection), which is signed and dated 1855 (Lawall, Documentary Catalogue, p. 112).

. On Durand’s response to Claude, see Huntington, Asher B. Durand, p. 29; Durand, Life and Times, pp. 147, 157, 158, 159-61; and John S. Caldwell, “Asher B. Durand: Travels in Europe, 1840-1841, and Their Role in His Artistic Development,” M.A. thesis, Hunter College, City University of New York, pp. 7-10.

Notes:

. Durand, Life and Times, p. 177.

2. “Fine Arts: National Academy of Design, Second Notice,” New York Herald, April 24, 1860, p. 2.

3. Lawall, Documentary Catalogue, pp. 193-94.

4. D. O. C. Townley, “Asher Brown Durand, Ex-President N.A.D.,” Scribner’s Monthly 2 (May 1871): 43.

5. Durand, Life and Times, p. 177.

6. Jonathan Sturges to A. B. Durand, April 5, 1870, quoted in Lawall, Documentary Catalogue, p. 128.

7. Daniel Huntington, Asher B. Durand: A Memorial Address (New York: Century Association, 1887), pp. 36-37.

8. See B[arbara] D. G[allati], “Early Morning at Cold Spring,” in John Howat et al., American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, exhib. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 9. The only other example among his located works that resembles the New Britain picture is a canvas known only as Landscape (private collection), which is signed and dated 1855 (Lawall, Documentary Catalogue, p. 112).

10. On Durand’s response to Claude, see Huntington, Asher B. Durand, p. 29; Durand, Life and Times, pp. 147, 157, 158, 159-61; and John S. Caldwell, “Asher B. Durand: Travels in Europe, 1840-1841, and Their Role in His Artistic Development,” M.A. thesis, Hunter College, City University of New York, pp. 7-10.

11. Durand, Life and Times, p. 177.

12. “Fine Arts: National Academy of Design, Second Notice,” New York Herald, April 24, 1860, p. 2.

13. Lawall, Documentary Catalogue, pp. 193-94.

14. D. O. C. Townley, “Asher Brown Durand, Ex-President N.A.D.,” Scribner’s Monthly 2 (May 1871): 43.

15. Durand, Life and Times, p. 177.

16. Jonathan Sturges to A. B. Durand, April 5, 1870, quoted in Lawall, Documentary Catalogue, p. 128.

Person Type(not assigned)