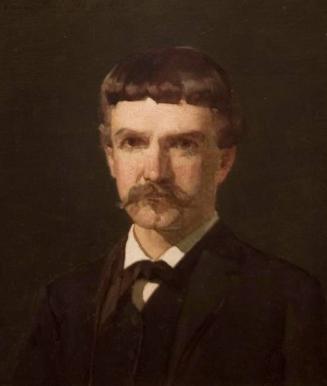

Richard LaBarre Goodwin

American, 1840 - 1910

Birth-PlaceAlbany, NY

Death-PlaceOrange, NJ

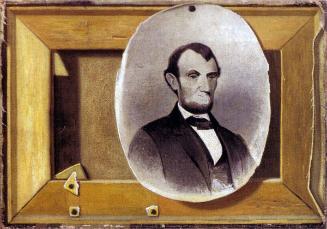

BiographyRichard LaBarre Goodwin (1840-1910)Born in Albany, New York, Richard LaBarre Goodwin was the son of Edwin Wyburn Goodwin, a portraitist of political notables who died when Richard was five. Richard's early training is uncertain; according to Alfred Frankenstein, he studied with "various obscure teachers, apparently in New York City," and became an itinerant portraitist in 1862. The Civil War briefly interrupted his career; he was wounded at the first battle of Bull Run and mustered out as disabled. He spent the next twenty-five years traveling through western New York State as an itinerant painter. He established a studio in Syracuse during the 1880s, where he may have begun concentrating on still life painting, but later resumed his travels. In Washington, D.C., between 1890 and 1893, Goodwin sold a number of canvases to California senators George Hearst and Leland Stanford. The artist also visited Chicago (during the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition), Colorado Springs, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Portland, Oregon. His final destination was Orange, New Jersey, where his younger son, Charles, was employed by Edison Labs. Goodwin settled there a few years before his death.

Goodwin's oeuvre includes endless variations on game, mostly birds, though he occasionally used a fox or a wild turkey. The simplest canvases are small groups of one or two birds hanging against a bare wall; the largest and most elaborate are arrangements of game hanging from the hunter's cabin door, complete with shotgun, hat, boots, canteen, powder horn, and other paraphernalia. Goodwin's most famous work of this type is his picture of Teddy Roosevelt's cabin door. At the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, Goodwin had seen the door of a hunting cabin in the Dakotas, where Roosevelt had stayed in 1890. Goodwin chose the door as a backround for his painting, which was to have been presented to Roosevelt himself by a group of Portlanders. The plan fell through, but Goodwin kept the picture, painted numerous replicas, and profited from its Roosevelt connections.

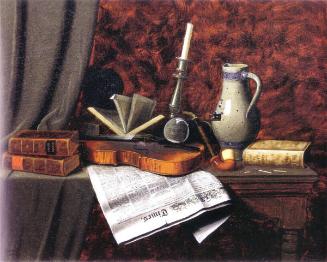

“Wild Game in the Kitchen”, ca. 1890

Oil on canvas, 55 ¾ x 35 3/4 in. (141.6 x 90.8 cm)

Signed (bottom center): “R LaBarre Goodwin”

Charles F. Smith Fund (1958.10)

“Wild Game in the Kitchen”

The fish and game still life came into vogue after the Civil War, perhaps as a reflection of the growth of urban culture, which led to a return to nature-based pursuits and the popularity of masculine activities in a era of gender separation. A number of still-life painters specialized in the genre--William Harnett, Alexander Pope, Jefferson David Chalfant, and George Cope.

A traveler and an outdoorsman, Goodwin painted a great number of game pieces. Of the more than seventy-five works known today, most are depictions of hanging game birds against a bare wall or a cabin door. “Wild Game in the Kitchen”, a variation of the Dutch seventeenth-century kitchen piece, is also typical of both Goodwin's oeuvre and the genre in general. A powder horn and trophies of the hunt hang from a peg against a bare wall. Various household items are arranged, seemingly at random, around the display of wild game. A china platter and a brass pitcher sit on the shelf; a bunch of sage, an aromatic herb used to dress wild game, hangs nearby. The pair of skeleton keys presumably opens the cupboard door, on which hangs a battered copy of the 1822 Farmers' Almanac. Goodwin's birds--a male wood duck, a prairie chicken, and a quail or partridge--fan out from the peg in a pyramid, the base of which is formed by a shallow wall shelf.

While most of Goodwin's canvases are highly repetitious, the New Britain painting has only one other known variation—“Kitchen Piece” (1890; Stanford University Museum). In this work a rabbit, a quail or grouse, and hunting paraphernalia hang against a plaster wall between a big brass ladle and a string of onions; below them is a shelf, similar to that in “Wild Game in the Kitchen”, only this time a candlestick and candle snuffer, a match, and a platter decorated with a medieval landscape lie on the shelf.

Goodwin, like Pope, Chalfant, and Cope, was influenced by Harnett's well-known “After the Hunt” pictures. (1) One of these canvases gained notoriety as "one of the most famous barroom pictures of its time in America" while hanging at Theodore Stewart's New York establishment, the Hoffman House. (2) Harnett painted the series shortly after his return from Europe in 1886, and the subject was widely imitated during the following decade. Some elements of Harnett's work, such as the floating feather, appear in Goodwin's paintings. Goodwin may have been inspired by Harnett, but he was only expanding the possibilities of an already favorite theme, for he had painted dead ducks hanging against plain backgrounds as early as 1880. Moreover, he may have known European treatments of the kitchen piece, especially those by seventeenth-century Dutch artists. (3)

MAS

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Alfred Frankenstein, “After the Hunt: William Harnett and Other American Still Life Painters”, rev. ed. (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969), pp. 131-35; William H. Gerdts and Russell Burke, “American Still-Life Painting” (New York, Washington, D.C., and London: Praeger Publishers, 1971), pp. 145, 156; William H. Gerdts, “Painters of the Humble Truth: Masterpieces of American Still Life, 1801-1939”, exhib. cat. (Columbia, Mo, and London: University of Missouri Press, 1981), pp. 193.

1. Frankenstein, “After the Hunt”, pp.132-33; and Gerdts and Burke, “American Still-Life Painting”, p. 145.

2. Gerdts, Painters of “ Humble Truth”, p. 177.

3. For a recent treatment of this theme, see Scott A. Sullivan, “The Dutch Gamepiece”: Allanheld and Schram, 1984).

Person Type(not assigned)