John Frederick Peto

American, 1854 - 1907

Death-PlaceIsland Heights, NJ

Birth-PlacePhiladelphia, PA

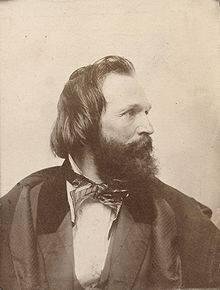

BiographyJohn Frederick Peto (1854-1907)Born in Philadelphia, John Frederick Peto was one of four children of Catherine and Thomas Peto, a gilder, picture-frame dealer, and volunteer fireman. As a child, Peto had a great interest in drawing and sketching. By 1876 he was listed in the city directory as a painter, and two years later he was recorded as a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. During the 1880s Peto maintained a studio on Chestnut Street, in the Philadelphia artists' district, and exhibited his still lifes at Earle's Gallery. He occasionally sent paintings to annuals of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia(1879-81; 1885-87) and to major art and industrial exhibitions in other cities.

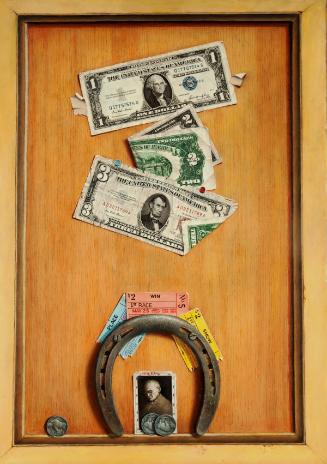

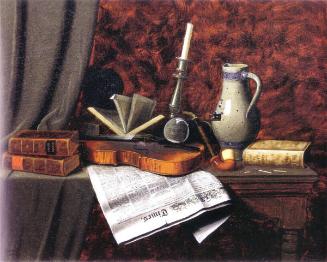

A fundamental influence on Peto's early career was probably the Philadelphia still-life tradition established by the Peale family. Perhaps most important was the example set by Peto's older colleague William Michael Harnett, who studied at the Pennsylvania Academy in the 1870s, maintained a studio near Peto's on Chestnut Street, and also sold his works through Earle's Gallery. Like Harnett and other still-life artists of their generation, Peto concentrated on man-made objects from everyday life, such as books, mugs, pipes, musical instruments, and rack paintings.

Around the time of his marriage, in 1887, Peto built a house and studio in Island Heights, New Jersey, and distanced himself from Philadelphia artistic life. By the time of his death he was virtually unknown; when his paintings were rediscovered thirty years later they were often sold as Harnett’s. Not until 1947, when Alfred Frankenstein discovered Peto's studio, which had remained basically intact since his death, was Peto established as one of the major figures in American still-life painting.

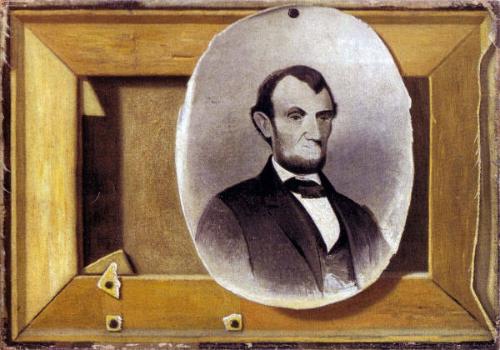

Lincoln and the Pfleger Stretcher, 1898

Oil on canvas, 10 x 14 in. (20.5 x 36.6 cm)

Signed, dated, and inscribed (verso): AN OLD MILL / J. F. PETO / 4.98 / ISLAND HEIGHTS / N.J.

Charles F. Smith Fund (1966.5)

Peto's subject matter can be divided into four basic categories: small kitchen still lifes, often arrangements of a few basic objects, such as pipes, mugs, jugs, dry biscuits, and bottles; library still lifes; arrangements of objects hanging on sections of walls or door panels; and office boards and rack pictures. The trompe-l'oeil device of an imaginary canvas back is less common. (1) Yet the engraved portrait of Abraham Lincoln is found in numerous late rack pictures by Peto.

“Lincoln and the Pfleger Stretcher” is one of seven known Petos that bear the inscription “An Old Mill” on the back. (2) One or two of these works do have pictures of an old mill on the back, reflecting Peto's common practice of reusing canvases. (3) According to Frankenstein, Peto was often short of cash and sold countless small works such as these "for whatever they would bring", about three or four dollars each. (4) The New Britain canvas was apparently among a stack of paintings Peto sold to his neighbor, James Bryant. (5)

The main subject of “Lincoln and the Pfleger Stretcher”, the canvas back, can be found in paintings by the seventeenth-century artist Cornelis Gysbrechts. It is not clear if Peto saw these earlier examples or if he invented the subject independently. (6) Like Gysbrechts, Peto's painted stretcher is realistically depicted from the surface textures of the wood and the curled edges of the canvas, to the remnants of a label, held by three tacks, and the shadow cast by the stretcher bar and the oval portrait. Peto used the Pfleger stretcher, patented in 1886, throughout his career; its distinctive beveled and beaded edges form a factor in distinguishing Petos from Harnetts. (7)

The successful illusionism of the stretcher is countered by the poorly executed Lincoln portrait. Peto copied the image from a popular J. C. Buttre engraving after a well-known Matthew Brady photograph but left it only a few brushstrokes from completion around the mouth. This unfinished aspect gives the portrait the tattered and worn quality of an old engraving.

The presence of the Lincoln portrait also adds a narrative, anecdotal dimension to the painting. While Peto’s trompe-l'oeil rack pictures incorporated photographs and memorabilia relating to the owners, works with the Lincoln image evoke a sense of haunting melancholy. Peto's obsession with the Lincoln image may have been related to the death of his own father, a Civil War veteran who died about 1895. (8) Yet in his almost obsessive use of the Lincoln image after 1894, Peto also may have been expressing the general fin-de-siècle malaise shared by many Americans. The tragedy of Lincoln's assassination and the nation's shattered self-confidence in the wake of the Civil War were common themes in turn-of-the-century prose by Walt Whitman and Stephen Crane, still lifes by Nicholas A. Brooks, George Cope, and Alexander Pope, and countless statues and monuments erected across the country in memory of the dead. (9)

MAS

Bibliography:

Alfred Frankenstein, John F. Peto, exhib. cat. (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum and Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, 1950); Alfred Frankenstein, “After the Hunt: William Harnett and Other American Still Life Painters, 1870-1900”, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1953: rev. ed. 1969), pp. 99-111; Alfred Frankenstein, “The Reality of Appearance: The Trompe l'Oeil Tradition in American Painting”, exhib. cat. (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1970); John Wilmerding, “Important Information Inside: The Art of John F. Peto and the Idea of Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century America”, exhib. cat. (New York: Harper and Row, 1983).

NOTES:

1. In his notes on Peto, Frankenstein mentions only a few examples of the canvas-back subject. One is almost identical to the New Britain work, except for a few minor changes: the image of Lincoln appears on a retangular card rather than as a painted oval portrait and the Pfleger stretcher has a slightly different torn label, now held by two tacks rather than three, and turned-over canvas edges. This work is signed “J. F. Peto” at the lower right (see Alfred Victor Frankenstein Papers, 1861-1980, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., reel 1377, frame 377).

2. Frankenstein, “After the Hunt”, p. 106.

3. Ibid.

4. Frankenstein, “John F. Peto”, p. 24.

5. The paintings sold to Bryant were passed down through his son-in-law Howard Keyser Jr. and to his children Howard, Cheston, and James, and to Mrs. William Wood (Frankenstein, “After the Hunt”, p. 106).

6. Frankenstein, “The Reality of Appearance”, p. 54.

7. Ibid., 100.

8. Wilmerding gives 1895 as the year of Thomas Hope Peto’s death, but the artist’s 1904 memento mori for his father gives the date 1896; reproduced in Wilmerding, “Important Information”, p. 14.

9. Ibid., pp. 194-204; and Robert F. Chirico, "Language and Imagery in Late Nineteenth-Century Trompe l'Oeil," “Arts Magazine” 59 (March 1985): 110-14.

Person Type(not assigned)