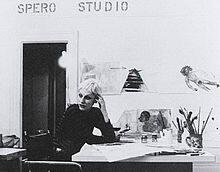

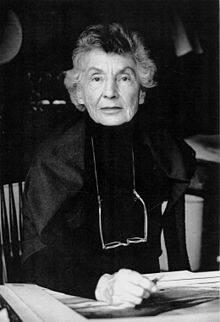

Nancy Spero

American, 1926 - 2010

Birth-PlaceCleveland, OH

Death-PlaceNew York, NY

BiographyNANCY SPERO(b. 1926)

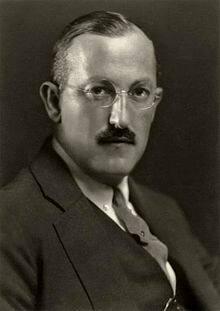

Nancy Spero was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1926. A year later her family moved to Chicago. After graduating from New Trier High School (1944) and studying for a year at the University of Colorado (1944−1945), Spero found her milieu at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She graduated with a BFA in 1949. Post-World War II Chicago, as the “second city,” was an artistic crossroads where diverse modernist approaches could be found: from cool Bauhaus abstraction to Jean Dubuffet’s raw, expressionist Art Brut. Spero’s figurative and expressionistic works from this period were informed by a constellation of ideas: French existentialist thought and its model of the activist individual; the immediacy of German Expressionism; and, Dubuffet’s anti-aesthetic stance, championing non-Western art, the art of children and what is currently termed “outsider art.” While studying at the Art Institute, she met a comrade-in-arms who shared her artistic and philosophical values, fellow student and painter, Leon Golub.

In the fall of 1949, Spero continued her studies in Paris, at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and at the Atelier of Andre Lhote, an early Cubist painter, teacher and critic. She returned from her studies in 1950, and in 1951 she married Golub and the couple settled in Chicago. Spero and Golub were equally committed to exploring a modernist representation of the human form, its narratives and art historical resonances, even as Abstract Expressionism was becoming the dominant idiom. With the support of a patron, the couple traveled to Italy, where they lived and painted in Florence and Ischia from 1956 to 1957. Finding a more varied, inclusive and international atmosphere in the contemporary art world of Europe, Spero and Golub moved to Paris, living there from 1959 to 1964. In 1962, Spero had her first solo exhibition in Paris at the Galerie Breteau. Working with mythic themes, such as mothers and children, lovers and prostitutes, Spero’s melancholic, and sometimes ferocious, Paris Black Paintings (1959-1964) contained spectral figures emerging and receding in a murky darkness.

In 1964 Spero and Golub returned to New York where they worked until his death in 2004. On their return, the Vietnam War was raging and the Civil Rights Movement was exploding. Affected by images of the war broadcast nightly on television and the unrest and violence evident in the streets, Spero began her “War Series” (1966-70). These small gouache and ink on paper, executed rapidly, explore the obscenity and destruction of war. An activist and early feminist, Spero was a member of the Art Workers Coalition (1968-69), Women Artists in Revolution (1969), and in 1972, she was a founding members of the first women’s cooperative gallery, A.I.R.(Artists in Residence) in Soho. It was during this period that Spero completed her “Artaud Paintings” (1969-70), finding her artistic “voice” and developing her signature scroll paintings: “Codex Artaud” (1971-1972). Uniting text and image, her long scrolls of paper, glued end-to-end and tacked on the walls of A.I.R., violated the formal presentation, choice of valued medium and scale of framed paintings.

In 1974, Spero chose to focus on themes involving women and their representation in various cultures; her “Torture in Chile” (1974) and the lengthy scroll, “Torture of Women” (1976, 20 inches x 125 feet), interwove oral testimonies with images of women throughout history, linking the contemporary governmental brutality by Latin American dictatorships (from Amnesty International reports) with the historical repression of women. The genesis of the content of the Museum’s “Desaparecidos” is to be found in the combined images and texts representing these “disappeared” women, victims of political terror, torture and murder.

Developing a pictographic language of body gestures and motion, a physical hieroglyphics, Spero reconstructed diverse representations of women from pre-history to the present. From 1976 through 1979, she researched and worked on “Notes in Time on Women”, a paper scroll measuring 20 inch by 210 feet. She elaborated and amplified this theme in “The First Language” (1979-81, 20 inches by 190 feet), eschewing text altogether in favor of an irregular rhythm of painted and collaged figures, thus creating her “cast of characters.” The acknowledgement of Spero’s international status as a preeminent figurative and feminist artist was signaled in 1987 by her traveling retrospective exhibitions in the U.S. and U.K. By 1988, she developed her first wall installations, To Soar, at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and Waterworks at The Filter Gallery, RC Harris Water Filtration Plant, Toronto. For these installations, Spero extended the picture plane of the scrolls by moving her images directly onto the walls of museums and public spaces.

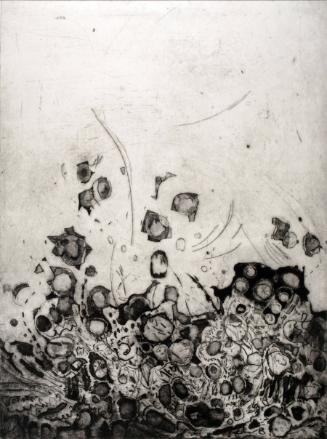

Desaparecidos

The title “Desaparecidos” refers to the “disappeared ones,” people abducted and imprisoned, or murdered, during the reign of terror of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in the 1970s and 1980s. The hemorrhage of violence against women, in particular, mass rape as a tactic of war, has been an on-going theme in Spero’s work since her “War Series” and “Torture of Women”. As the British art historian and theorist, Jon Bird, writes, “It is hard to find other representations in the history of art that convey such furious condemnation – perhaps Goya’s “Disasters of War”, Otto Dix’s etchings of trench warfare, or an earlier tradition, one referenced by Spero herself, the medieval “Beatus Apocalypse of Gerona” depicting the wars of angels and demons and the horrific fate of non-believers.”(1)1

In the five panel work on paper “Desaparecidos”, the artist achieves multiple effects that give the impression of an ancient rubbing brought to the surface, a fugitive archaic commemoration. Spero willfully creates a sense of uncertainty and unease. Three middle panels of blue handmade paper are flanked by two outer panels of white handmade paper, suggesting a symmetry, but each piece of paper is a different size and each is oriented on a different plane. Reminiscent of a classical frieze, the format implies a narrative that might be “read” from left to right, or right to left, but the images fade in and out of focus, appearing and disappearing, becoming indecipherable as a narrative. The work embodies, structurally, the theme of the “disappeared” and the disappearance of women from written histories in general.

The left-hand panel has a mottled and highly textured ground printed in coppery umbers and the rusty color of dried blood. On top of this ground hovers a hand-printed doubled figure of a grainy mud color. While the twin figures are printed from the same plate, the left figure is a ghost-like faded image and the right figure appears to have the depth and solidity of a bas-relief. Head in profile and body frontal, the hybrid figure evokes an Egyptian tomb goddess merged with a newspaper clipping of a woman in a simple dress, too indistinct to identify accurately apear scratched over the surface: “Beatiz,” “30,” a faded date and surname. Spero combines a phototransfer from the pages of Amnesty International publication with an image from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, a powerful Hathor or Mut figure with the head of a lioness and the body of a human,2 linking cultures and time frames.(2)

The second and fourth panels at first appear nearly identical: both printed on blue paper, forming a frieze-like procession of mourning matrons in white. As if in a photonegative, the draped linear figures seem apparitions floating on sea-blue paper. The image derives from classical Roman sarcophagi carved with mourning figures. In profile, with classical drapery from head-to-toe, a single mourning figure is repeatedly hand-printed with subtle differences of pressure and ink application. As in a cinematic freeze-frame, the figures suggest movement in a rhythmical repetition, and their forms mingle with a wave-like indeterminate ground of transparent white ink over blue paper. The overall sweep of textures and linear rhythms, with the profiles moving right to left, invoke a transformative underworld passage.

The middle panel weaves repeated and overlapping images of three figures in a staccato rhythm: an Egyptian vulture goddess often found on tomb walls, a PreColumbian mummified or skeletal head, and a cursive, linear hieroglyph of Nekhebet, queen of the underworld, a guide and protector.(3)3 Printed in golden yellow ink over blue paper, the images evoke the ceremonial gold and lapis lazuli used by the ancient Egyptians, and refer again to the artist’s referencing “the body [as] a symbol and a hieroglyph, in a sense, an extension of language.”(4)4 Different versions of the vulture goddess have appeared in Spero’s work since “Torture of Women”, and they usually superimpose several points of view and moments in time: the head in profile, one wing seen from above, and the other wing and tail seen from below. What seems like a frozen moment of flight actually represents several moments of flight seen simultaneously.(5)5 Transitory states are implied by the fanning wing beats; the relief-like mummy heads appear to drift as Nekhebeit glides in and out of view. Spero suggests both mortality and immortality, a journey of passage and metamorphosis.

Contrasting the metaphysical implications of the three middle panels, the one on the right is a stark phototransfer from the pages of Amnesty International’s reports on the victims of governmental terrorism. Printed at the bottom of the panel in a dense indigo over a ground of clotted reds lies the corpse of a woman laid in a coffin angled obliquely away from the picture plane. Above the figure are thickly inked roller marks, weighing the image downward. The brutal content of the image is intensified by the handling of the colored inks on the delicate surface. Subverting any single meaning or reference, Spero mines history and contemporary events to stimulate multiple interpretations.

DF

Bibliogrphy

Jon Bird and Lisa Tickner, “Nancy Spero”, exhib. cat. (London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1987); Dominique Nahas, ed., “Nancy Spero: Works Since 1950”, exhib. cat. (Syracuse, New York: Everson Museum of Art, 1987); Hanne Weskott, “Nancy Spero in der Glyptothek, Arbeiten auf Papier, 1981-1991”, exhib. cat. (Munich: Glyptothek am Koenigsplatz Muenchen, 1991); Linda Julian, ed., “Nancy Spero, 1993 Emrys Journal”, exhib. cat. (Greenville, SC: Greenville County Museum of Art, 1993); Susan Harris, “Nancy Spero”, exhib. cat. (Malmo: Malmo Konsthall, 1994); Jon Bird, Jo Anna Isaak, and Sylvere Lotringer, “Nancy Spero” (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1996); Elizabeth A. Macgregor and Catherine de Zegher, “Nancy Spero”, exhib. cat., (Birmingham, U.K.: Ikon Gallery, 1998).

Person Type(not assigned)

Terms