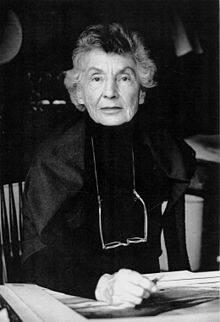

Tom Wesselmann

American, 1931 - 2004

Birth-PlaceCincinnati, OH

BiographyTom Wesselmann (February 23, 1931, Cincinnati – December 17, 2004) was an American artist associated with the Pop art movement who worked in painting, collage and sculpture. From 1949 to 1951 he attended college in Ohio; first at Hiram College, and then transferred to major in Psychology at the University of Cincinnati. He was drafted into the US Army in 1952, but spent his service years stateside. During that time he made his first cartoons, and became interested in pursuing a career in cartooning. After his discharge he completed his psychology degree in 1954, whereupon he began to study drawing at the Art Academy of Cincinnati. He achieved some initial success when he sold his first cartoon strips to the magazines 1000 Jokes and True.Cooper Union accepted him in 1956, and he continued his studies in New York. During a visit to the MoMA he was inspired by the Robert Motherwell painting Elegy to the Spanish Republic: “The first aesthetic experience… He felt a sensation of high visceral excitement in his stomach, and it seemed as though his eyes and stomach were directly connected”.[1]

Wesselmann also admired the work of Willem de Kooning, but he soon rejected action painting: “He realized he had to find his own passion he felt he had to deny to himself all that he loved in de Kooning, and go in as opposite a direction as possible."[2]

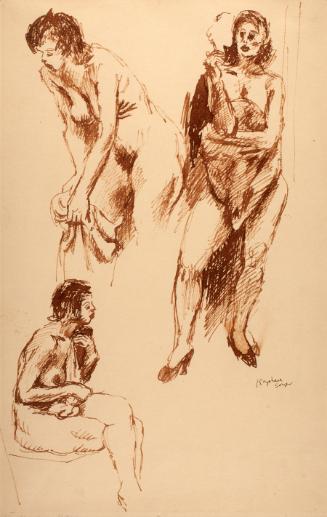

In 1957 Wesselmann met Claire Selley, another Cooper Union student who was to become his friend, model, and later, his wife. 1958 was a pivotal year for Wesselmann. A landscape painting trip to Cooper Union's Green Camp in rural New Jersey, brought him to the realization that he could pursue painting, rather than cartooning, as a career.[3] 1959-1964 - After graduation Wesselmann became one of the founding members of the Judson Gallery, along with Marc Ratliff and Jim Dine, also from Cincinnati, who had just arrived in New York. He and Ratliff showed a number of small collages in a two-man exhibition at Judson Gallery. He began to teach art at a public school in Brooklyn, and later at the High School of Art and Design.

Wesselmann's series Great American Nude (begun 1961) first brought him to the attention of the art world. After a dream concerning the phrase "red, white, and blue", he decided to paint a Great American Nude in a palette limited to those colors and any colors associated with patriotic motifs such as gold and khaki.[4] The series incorporated representational images with an accordingly patriotic theme, such as American landscape photos and portraits of founding fathers. Often these images were collaged from magazines and discarded posters, which called for a larger format than Wesselmann had used previously. As works began to approach a giant scale he approached advertisers directly to acquire billboards. Through Henry Geldzahler Wesselmann met Alex Katz, who offered him a show at the Tanager Gallery. Wesselmann's first solo show was held there later that year, representing both the large and small Great American Nude collages. In 1962 Richard Bellamy offered him a one-man exhibition at the Green Gallery. About the same time, Ivan Karp of the Leo Castelli Gallery put Wesselmann in touch with several collectors and talked to him about Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist’s works. These Wesselmann viewed without noting any similarities with his own {S. Stealingworth, p. 25}.

While not a cohesive movement, the idea of Pop Art (a name coined by Lawrence Alloway and others) was gradually spreading among international art critics and the public. In As Henry Geldzahler observed: “About a year and a half ago I saw the works of Wesselmann..., Warhol, Rosenquist and Lichtenstein in their studios (it was more or less July 1961). They were working independently, unaware of each other, but drawing on a common source of imagination. In the space of a year and a half they put on exhibitions, created a movement and we are now here discussing the matter in a conference. This is instant history of art, a history of art that became so aware of itself as to make a leap that went beyond art itself”.[5]

The Sidney Janis Gallery held the New Realists exhibition in November 1962, which included works by the American artists Jim Dine, Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, George Segal, and Andy Warhol; and Europeans such as Arman, Enrico Baj, Christo, Yves Klein, Tano Festa, Mimmo Rotella, Jean Tinguely, and Mario Schifano. It followed the Nouveau Réalisme exhibition at the Galerie Rive Droite in Paris, and marked the international debut of the artists who soon gave rise to what came to be called Pop Art in Britain and The United States and Nouveau Réalisme on the European continent. Wesselmann took part in the New Realist show with some reservations,[6] exhibiting two 1962 works: Still life #17 and Still life #22.

Wesselmann never liked his inclusion in American Pop Art, pointing out how he made an aesthetic use of everyday objects and not a criticism of them as consumer objects: “I dislike labels in general and 'Pop' in particular, especially because it overemphasizes the material used. There does seem to be a tendency to use similar materials and images, but the different ways they are used denies any kind of group intention”.[7]

That year, Wesselmann had begun working on a new series of still lifes. experimenting with assemblage as well as collage. In Still Life #28 he included a television set that was turned on, “interested in the competitive demands that a TV, with moving images and giving off light and sound, can make on painted portions” [8] He concentrated on the juxtapositions of different elements and depictions, which were at the time truly exciting for him: “Not just the differences between what they were, but the aura each had with it... A painted pack of cigarettes next to a painted apple wasn’t enough for me. They are both the same kind of thing. But if one is from a cigarette ad and the other a painted apple, they are two different realities and they trade on each other... This kind of relationship helps establish a momentum throughout the picture... At first glance, my pictures seem well behaved, as if – that is a still life, O.K. But these things have such crazy give-and-take that I feel they get really very wild”.[7] He married Claire Selley in November 1963.

In 1964 Ben Birillo, an artist and business partner of gallery owner Paul Bianchini, contacted Wesselmann and other Pop artists with the goal of organizing The American Supermarket at the Bianchini Gallery in New York. This was an installation of a large supermarket where Pop works (Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup, Watts’s colored wax eggs etc.) were shown among real food and neon signs. In the same year Wesselmann began working on landscapes, including one that includes the noise of a Volkswagen starting up. The first shaped canvas nudes also appeared this year.[9]

1965-1970

His works in these years: Great American Nude #53, Great American Nude #57, show an accentuated, more explicit, sensuality, as though celebrating the rediscovered sexual fulfilment of his new relationship.[10] He carried on working on his landscapes, but also made the Great American Nude #82, reworking the nude in a third dimension not defined by drawn lines but by medium: molded Plexiglas modeled on the female figure, then painted. His compositional focus also became more daring, narrowing down to isolate a single detail: the Mouth series began in 1965, his Seascapes began the following year. Two other new subjects also appeared: Bedroom Painting , and Smoker Study, the latter of which developed from observation of his model for the Mouth series. The Smoker Study series of works would become one of the most recurrent themes in the 1970s.[11]

Beginning in 1965, Wesselmann made several studies for seascapes in oil while vacationing in Cape Cod and upstate New York. In his New York City studio, he used an old projector to enlarge them into large-format works. This series of views, called the Drop-Out series were constructed from the negative space around a breast. The breast and torso frame one side of the image while the arm and the leg form the other two sides. This series of works would become one of the most recurrent themes in the 1970s.[11] He started working on shaped canvases and opted for increasingly large formats.

He worked constantly on the Bedroom Painting series, in which elements of the Great American Nude, Still Lifes and Seascapes were juxtaposed. With these works Wesselmann began to concentrate on a few details of the figure such as hands, feet, and breasts, surrounded by flowers and objects. The Bedroom Paintings shifted the focus and scale of the attendant objects around a nude; these objects are small in relation to the nude, but become major, even dominant elements when the central element is a body part. The breast of a concealed woman appeared in a box among Wesselmann's sculpted still life elements in a piece entitled Bedroom Tit Box, a key work that “...in its realness and internal scale (the scale relationships between the elements) represents the basic idea of the Bedroom Painting”.[12] He made Still Life #59, five panels that form a large, complex dimensional, freestanding painting: here too the elements are enlarged, and part of a telephone can be seen. A nail-polish bottle is tipped up on one side, and there is a vase of roses with a crumpled handkerchief next to it, and the framed portrait of a woman, actress Mary Tyler Moore, whom Wesselmann considered as the ideal prototype girlfriend. These are works in which he made more recognizable portraits, with a less anonymous feel. In Bedroom painting #12 he inserted a self-portrait. Still Life #60 appeared in 1974: the monumental outline, almost 26 feet (eight meters) long, of the sunglasses acts as a frame for the lipstick, nail polish and jewelry; a microcosm of contemporary femininity that Wesselmann took to the level of gigantism. His Smokers continued to change: he introduced the hand, with polished fingernails sparkling in the smoke.[13] In 1973 he brought to an end the series devoted to the Great American Nude with "The Great American Nude #100." But of course the incontrovertible sensuality of Wesselmann’s nudes was constantly accompanied by an ironic guiding thread that was clearly revealed in the artist’s own words: “Painting, sex, and humor are the most important things in my life." [14]

In 1978 Wesselmann started work on a new series of Bedroom Paintings. In these works he revised the formal construction of the composition, which was now cut by a diagonal, with one entire section being taken up by a woman’s face in the very near foreground. In 1980 Wesselmann published the monograph Tom Wesselmann, an autobiography written under the pseudonym Slim Stealingworth. His second daughter, Kate, was born; previous children were Jenny and Lane.

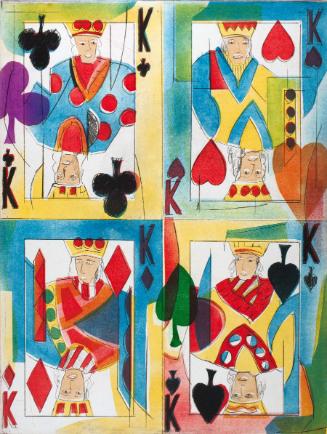

In 1983 Wesselmann was seized by the idea of doing a drawing in steel, as if the lines on paper could be lifted off and placed on a wall. Once in place the drawings appeared to be drawn directly on the wall. This idea preceded the available technology for lasers to mechanically cut metal with the accuracy Wesselmann needed. He had to invest in the development of a system that could accomplish this, but it took another year for that to be ready. The incorporation of negative space that had begun in the Drop-Out series was continued into a new medium and format. They started out as works in black and white, enabling him to redevelop the theme of the nude and its composition.[15] Wesselmann took his idea further and decided to make them in color as well. As well as colored metal nudes, in 1984 he started working on rapid landscape sketches that were then enlarged and fabricated in aluminum.

Obliged by the use of metals to experiment with various techniques, Wesselmann cut works in aluminum by hand; for steel he researched and developed the first artistic use of laser-cut metal. Computerized imaging had not yet been developed. His metal works continued to go through a constant metamorphosis: My Black Belt, 1990, a seventies subject, acquired a new vivacity that forcefully defined space in the new medium. The Drawing Society produced a video directed by Paul Cummings in which Wesselmann makes a portrait of a model and a work in aluminum.

“Since 1993 I’ve basically been an abstract painter. This is what happened: in 1984 I started making steel and aluminum cut-out figures... One day I got muddled up with the remnants and I was struck by the infinite variety of abstract possibilities. That was when I understood I was going back to what I had desperately been aiming for in 1959, and I started making abstract three-dimensional images in cut metal. I was happy and free to go back to what I wanted: but this time not on De Kooning’s terms but on mine".[16] In this new abstract format Wesselmann preferred a random approach, and made compositions in which the metal cut-outs resembled gestural brushstrokes. His nudes on canvas of this period rework 1960s images. They, “[Constitute] an unexpected but highly satisfying nostalgic return to a youthful episode in the very midst of one of the most radical changes of style in Wesselmann’s career. Self-contained and complete in themselves, they seem more likely to stand alone rather than to lead to further reinterpretations of Sixties motifs. In other words they should not be taken as a sign that Wesselmann is embarking on an extended re-engagement with his classic Pop phase...”.[17] In 1999 he made his final Smoker work, Smoker #1 (3-D), as a relief in aluminum. In the last ten years Wesselmann's health was worsened by heart disease, but his studio work remained constant.

The abstract works display firmer lines and a chromatic range that favored primary colors. Wesselmann acknowledged the influence of Mondrian by choosing titles that recall the earlier painter's works: New York City Beauty (2001). In these years the influence of Matisse diminished the border between Wesselmann's figurative and abstract styles. In 1960 Wesselmann had been able to view the works of the French master in person at the MoMA's Gouaches Découpées (Gouache Cut-outs) exhibition, and forty years later paid homage in his Sunset Nudes series. In Sunset Nude with Matisse, 2002, he inserted Matisse's painting La Blouse Roumaine (1939–1940). Wesselmann also derived works from Matisse's cut-outs: Blue Nude (2000), initiated a series of blue nude reliefs sculpted in shaped aluminum.

Following surgery for his heart condition, Tom Wesselmann died on December 17, 2004. His last major paintings of the series Sunset Nudes (2003/2004) were shown after his death at the Robert Miller Gallery in New York in April 2006.[18]

The years following Wesselmann’s death were marked by a renewed interest in his work. Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma (MACRO) exhibited a retrospective in 2005, accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue. The following year L&M Arts in New York held a major exhibition of works from the 1960s. Two galleries; Maxwell Davidson and Yvon Lambert, jointly showed the Drop-Out series in New York in 2007. This coincided with the release of a new monograph on the artist, written by John Wilmerding and published by Rizzoli; Tom Wesselmann, His Voice and Vision. Another show, in 2010 by Maxwell Davidson, Tom Wesselmann: Plastic Works, was the first ever survey of Wesselmann’s work in formed plastic. A lifetime retrospective of drawings, Tom Wesselmann Draws, was shown at Haunch of Venison Gallery, New York, and then traveled to The Museum of Fine Art, Fort Lauderdale, FL, at Nova Southeastern University, and The Kreeger Museum in Washington, DC. A lifetime retrospective, to travel in North America, will open at The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in May, 2012.

REFERENCES

(S. Stealingworth, p. 12)

Jump up ^ (S. Stealingworth, 1980, p.15)

Jump up ^ (cf. S. Stealingworth, p.12)

Jump up ^ (S. Stealingworth, 1980 p. 20)

Jump up ^ (H. Gelzadher, in Arts Magazine, 1963, p. 37)

Jump up ^ (cf. S. Stealingworth, 1980, p. 31)

^ Jump up to: a b (interview with G. Swenson, ARTnews, 1964, p. 44)

Jump up ^ (S. Stealingworth, 1980, p. 16.)

Jump up ^ Paul Bianchini's Obituary, International Herald Tribune September 12, 2000, retrieved August 20, 2008

Jump up ^ (cf. M. Livingstone, 1996)

^ Jump up to: a b (S. Stealingworth, 1980, p. 52)

Jump up ^ (S. Stealingworth, 1980, p. 64)

Jump up ^ He started using photographs he took of his friend and model Danielle in order to make works in oils (ibid., p. 66)

Jump up ^ (interview with Irving Sandler, 1984)

Jump up ^ “These work began when I was drawing negative drop-out shapes from the model, and for the first time I put two shapes in relation to each other, an arm shape and a leg shape. Then I thought it would be interesting to connect them with a body line… this began the works with interior lines continuing outside the painting" (S.Hunter, 1993, pp. 27-28)

Jump up ^ interview with E. Giustacchini, Stile Arte, 2003, p. 29

Jump up ^ M. Livingstone, 1999, p. 6

Jump up ^ Tom Wesselmann at the Robert Miller Gallery, ARTINFO, April 22, 2006, retrieved 2008-04-24

Person Type(not assigned)