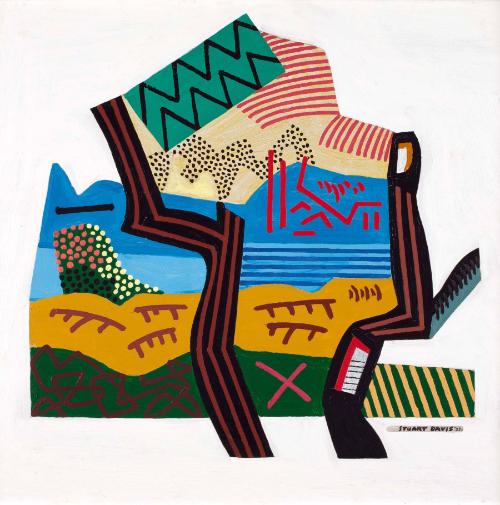

Analogical Emblem Landscape

Artist

Stuart Davis

American, 1894 - 1964

Date1933

MediumOil on composition board

DimensionsFrame: 20 1/4 × 21 × 1 3/4 in. (51.4 × 53.3 × 4.4 cm)

Image: 13 7/8 × 14 3/4 in. (35.2 × 37.5 cm)

Image: 13 7/8 × 14 3/4 in. (35.2 × 37.5 cm)

Credit LineOlga H. Knoepke Fund and Members Purchase Fund

Object number1996.16

On View

On view