William Michael Harnett

William Michael Harnett (b. Ireland, 1848-1892)

William Harnett, the son of an shoemaker, was born in County Cork and moved to Philadelphia with his family a year later. Trained as an engraver, he expanded his skills by taking art classes, first at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia and later at the Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design in New York. About 1875 he gave up engraving for oil painting. While Harnett's classes had focused on drawing the human figure, both from the antique and from live models, his first paintings depict fruit and other edibles. The artist later claimed he chose this subject because he could not afford to hire live models.

Harnett's early still lifes also reflect leisure pursuits: smoking scenes comprise small displays of pipes, tobacco, biscuits, and newspapers; writing tables feature newspapers, books, letters, and writing instruments. In these small, simple, intimate compositions, Harnett arranged the objects to suggest recent use. He also tried his hand at depicting paper currency; his success prompted a visit by U.S. Treasury officers, who warned him about the dangers of counterfeiting.

In 1880 Harnett traveled to Europe to continue his studies. After brief stays in London, Paris, and Frankfurt, he eventually settled in Munich, where he exhibited with the group of artists called the Kunstverein. Although his European study did not radically change his painting style or technique, it left an unmistakable influence upon his subject matter. Most obvious was the appearance of European newspapers--the “London Times”, “Le Figaro”--and the subject of hunting paraphernalia hanging against a door. During his German sojourn Harnett began assembling the large collection of curios that he would use as props for the remainder of his career.

After his return to the United States in 1886, Harnett quickly became one of the most popular still-life artists of his time. Even though his realistically executed canvases were virtually ignored by nineteenth-century art critics, who deemed his work pure imitation and thus not art, their arrangements of man-made commodities and objects from daily life found ready patrons in America's self-made businessmen and influenced an entire generation of artists who adapted his style and subjects to their own work.

Still Life with Violin, 1886

Oil on canvas, 19 7/8 x 23 7/8 in. (50.5 x 60.6 cm)

Signed and dated (lower left): [monogram] WMHARNETT. / 1886.

Grace Judd Landers Fund (1942.11)

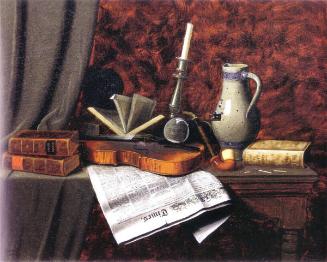

“Still Life with Violin”, painted soon after the artist's return from Europe, displays many elements associated with his tabletop arrangements. The objects are placed on a large table in front of a dark backdrop. An old violin rests on a copy of the Philadelphia Times from Wednesday morning, October 20, 1886. Nearby are a meerschaum pipe and a few used matches, a stoneware pitcher, a roll of sheet music, a tilted candlestick, and several books, including an open volume with a curious dog-eared leaf. The newspaper is thrust to the extreme frontal plane--a typical trompe l'oeil device that heightens the sense of illusion. The dark heavy drapery provides a certain focal point at the left, but otherwise the background is ambiguous. The arrangement has both an air of immediacy and a sense of permanency; book, pipe, and matches seem to have just been set aside, yet the pile seems to be accumulating slowly.

Alfred Frankenstein surmised that Harnett was fascinated by books,their shape, color, and texture,but that "what the book may signify as a work of poetry or prose does not concern him in the least."(1) Yet the artist himself always maintained that his pictures were intended to tell a story.(2) Many of Harnett's paintings after 1882 contain a ubiquitous vellum-covered book, most often Dante's “Divine Comedy” or one of Shakespeare's plays.(3) Dante's poem, which deals with themes of courtly love, chivalry, death, and resurrection, represents the “primary nexus of Harnett's literary focus."(4) Harnett often paired Dante's image or his works with references to his precursors Ovid, Petrarch, and Chaucer or to later writers Sir Walter Scott, Jane Porter, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.(5) In “Still Life with Violin”, Dante's “Purgatorio”, dated 1503, appears with a volume by the Scottish romantic poet Robert Burns. (The title of the third volume is indiscernible.)

One-quarter of Harnett's works touch upon music.(6) The violin occupies a significant position in many paintings, from tabletop arrangements like “Still Life with Violin” to more complex vertical displays, most notably “The Old Violin” (1886 private collection). Harnett preferred to depict old objects, those that exhibited "the mellowing effect of age."(7) These were no doubt more interesting to paint but also carried with them rich associations, evoking an atmosphere of nostalgia for the past.

The accumulations of books, instruments, and bric-a-

brac,disparate items gathered from various cultures and time periods, speaks to the Victorian mania for collecting. Still life paintings were often hung in studios, libraries, or sitting rooms among the types of objects they depicted. Significantly, in contrast to these antique objects, the daily newspaper comments directly on contemporary culture.(8) Thus, Harnett's paintings attracted patrons who were both nostalgic and progressive. Most of Harnett's patrons were men; many were businessmen, avid newspaper readers, and frequent advertisers. Moreover, many had specific connections to the newspaper business as publishers, editors, and writers. Peter Samuel Dooner, who owned “Still Life with Violin”, worked as a pressman at the “Illustrated New Age” and at the Philadelphia “Times” for a total of fourteen years.(9) About 1876 he opened his own hotel and saloon, a successful establishment for the next half century,(10) where he proudly displayed Harnett's “Still Life with Violin” and “Just Dessert” (1892; Art Institute of Chicago), a still life with grapes, a halved coconut, and a bottle of maraschino liqueur. Dooner was both a patron and a friend to Harnett: both were members of the Hibernian Society, an organization of Irish immigrants in Philadelphia, and Dooner was among the few friends present at Harnett's funeral. (11)

MAS

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Alfred Frankenstein, “After the Hunt: William Harnett and Other American Still Life Painters”, rev. ed. (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1969); Doreen Bolger, Marc Simpson, and John Wilmerding, eds., “William M. Harnett” (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992).

NOTES:

. Frankenstein, “After the Hunt”, p. 40.

2. Harnett, quoted in ibid., p. 55.

3. Such a blank vellum book was found in Harnett's estate.

4. Judy L. Larson, "Literary References in Harnett's Still Life Paintings," in Bolger, Simpson, and Wilmerding, eds., “William M. Harnett”, p. 267.

5. Ibid.

6. See Marc Simpson, "Harnett and Music: Many a Touching Melody, " in ibid., p. 289.

7. Harnett, quoted in Frankenstein, “After the Hunt”, p.56.

8. On Harnett's use of newspaper, see Laura Coyle, "'The Best of Modern Life': Newspapers in the Artist's Work," in Bolger, Simpson, and Wilmerding, eds., “William Harnett”, pp. 223-31.

9. Doreen Bolger, "The Patrons of the Artist: Emblems of Commerce and Culture," in ibid., p. 75.

10. Christopher Morley and T. A. Daly, “The House of Dooner: The Last of the Friendly Inns” (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1928). One obituary considered Dooner’s paintings two of Harnett’s best works; The innkeeper reportedly paid several hundred dollars for “Still Life with Violin”, and “since then $2,000 has been refused for this small gem”; see undated clipping, Blemly scrapbook, Alfred Frankenstein Papers, 1861-1980, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., reel 1374, frame 341.

11. Harnett’s election to the society in 1890 was through Dooner’s nomination; see Bolger, “Patrons of the Artist,” p.83 n. 6. At Harnett’s New York funeral, “among the few present were E. T. Snow, Peter Dooner and William T. Blemley, William T. Blemly Jr., and Cornelius Sheehan of New York” (William M. Harnett Buried: Only the Painter’s Intimate Friends Attended the Service,” undated clipping, Blemly scrapbook, roll 1374, frame 341).