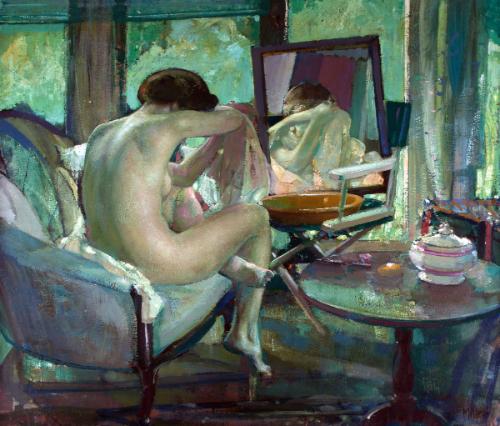

Summer Bather

Artist

Richard Edward Miller

(American, 1875 - 1943)

Datec. 1939

MediumOil on wood panel

Dimensions36 x 38 in. (91.4 x 96.5 cm)

ClassificationsOil Painting

Credit LineGift of Lawrence McCoy

Terms

Object number1951.16

DescriptionAs a student at Washington University's Saint Louis School of Fine Arts in the mid-1890s, Richard Miller was awarded prizes for doing the best work in life class from "nude and draped" models.1 It was not until thirty years later, after establishing a successful career as a painter of portraits and of decoratively dressed women in sun-dappled interiors, that Miller returned to painting the nude. There were some nudes along the way, most notably an entry in the 1912 Paris Salon in a style that crossed between Titian's and Renoir's entitled "Nude". It was sent to museum exhibitions in America, winning the Potter Palmer prize at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1914. It also created a flap: an official of the Chicago Police Department, judging it "vulgar," banned reproductions of it from appearing in shop windows, and the city's postmaster proscribed their being sent through the mail.2 Miller's inability to sell the painting until 1917 may have reined in any further inclination on his part to continue the painting of nudes in any significant number.3 Certainly his return from France to America, a country with an uneasy history of the nude in art stemming from cultural and social restrictions preventing artists from pursuing this subject freely, would have had an additional dampening influence on him.4In the interim Miller never completely abandoned the subject. About 1918 he painted a partially draped nude that anticipates "Summer Bather".5 In images of this unlocated work, the figure leans to the right, her bare back gently curving in the decorous manner gleaned from Japanese prints, an early influence on Miller's work.6 Miller's signature round tea tray rests at her side, as well as assorted blinds, drapes, and flowered fabrics, the artist's customary vehicles for the exploration of color, light, and texture. Written accounts describe the painting as a study in blue and green--the predominant tones in "Summer Bather".7 Although "Summer Bather" also recalls "The Venetian Blind" by Edmund Tarbell (ca. 1904; Worcester Art Museum, Mass.) and William McGregor Paxton's "Nude" (1915; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Miller's work goes far beyond their focus on the body. As Miller develops the genre, single classically modeled figures are enveloped in increasingly painterly, abstractly conceived, and brushed interiors, which become as aesthetically interesting as the figure.

It was not until Miller felt financially and professionally secure, from the mid-1930s on, that he allowed himself to return wholeheartedly to the genre.8 By the time he painted "Summer Bather", the nude subject had been enjoying a brief revival in American art.9 A reviewer, commenting on the painting as it appeared in the Corcoran Gallery of Art's Biennial that year, could write: "There is nothing more beautiful than the nude figure." And yet, a trace of the old skittishness around the subject is injected as she continues: "and, in the proper environment, nothing more chaste;as for instance the "Summer Bather" by Richard Miller in this exhibition.10 Whether or not one would characterize the figure as chaste, it is possible, neverthless, to understand what the writer means, for this is not a painting about the female as a sexual being. Rather it is about the formal concerns of painting, composition, color, line, and texture, which in this case have resulted in a highly sensual work: one that is also quite modern.

Formal concerns were an early focus of Miller, who trained as Whistler's "art for art's sake" held international sway.11 He himself pronounced: "Art's mission is not literary, the telling of a story, but decorative, the conveying of a pleasant optical sensation."12 "Summer Bather" is an exercise in the creation of a rich optical sensation. It is one of Miller's most compositionally complex canvases, its interlocking parts both anchoring and energizing the composition, revealing why Miller was so often praised for his strong sense of design.13 There is a lively interplay of human and man-made forms and textures. The prominent rectangular shape of the mirror is quietly echoed by the positioning of the figure's raised arm, back, and right thigh. A series of smaller rectangles (the windows, drapes, blinds, deck chair, a foot) are juxtaposed with circular shapes (the washbowl, round table, porcelain pot, and figure's head). The curved back of the figure follows the sweep of the sofa arm and back. Here and there a triangle appears: the figure's arms in the mirror and the chair legs beneath it.

Although Miller pays attention to the edges of his forms, within those linear boundaries he gives a looser rein to palette and brush. Polished and glazed surfaces gleam with light and reflections. Although the dominant color note is an aquatic blue-green, subtle nuances of color play over every square inch of canvas. Thick dabs of paint and thin washes coexist. Both ends of the paintbrush appear to have been used. Miller's mundane tabletop becomes as richly suggestive as a Monet water lily pond. Miller was very influenced by Impressionism. He met Monet during his sojourns in Giverny from 1907 on, the period during which he adopted Impressionism's high-key palette and broken brushwork. While his late work, such as "Summer Bather", becomes more tonal, Miller retained the energetic, spontaneous brushwork and strong interest in color that was part of Impressionism's legacy to him.

The figure itself is softly contoured yet has the firm luminous flesh of a classical marble statue. This classicizing is deliberate. The idealization of the figure (with hidden face preventing individual identity) announces its artificiality. As such the figure is emblematic of the entire canvas: presenting the world of art, not life. This is an unsentimental approach to painting, modern in sensibility. One is reminded of the Degas series of Bather pastels executed in a comparable spirit. We can more readily see this than Miller's contemporaries could at the end of his life, when his work was often dismissed for being too conservative. Having ties to the past does not preclude openness to the future.

MLK

Bibliography:

Wallace Thompson, "Richard Miller: A Parisian-American Artist," Fine Arts Journal 27 (November 1912): 709-14; Vittorio Pica, "Artisti contemporanei: Richard Emile Miller," Emporium 39 (March 1914): 162-77; Mabel Urmy Seares, "Richard Miller in a California Garden," California Southland 38 (February 1923): 10-11; Robert Ball and Max W. Gottschalk, Richard E. Miller, N.A.: An Impression and Appreciation (Saint Louis: Longmire Fund, 1968); Marie Louise Kane, A Bright Oasis: The Paintings of Richard E. Miller, exhib. cat. (New York: Jordan-Volpe Gallery, 1997).

NOTES:

1. The "Catalogue of the Officers and Students in Washington University with the Courses of Study for the Academic Year 1894-95" (p. 118) lists Miller as recipient of the Silver Medal for the "best work in life class, in black and white." The catalogue for the academic year 1896-97 (p. 96) lists him as the recipient of the Gold Medal for the "best work in life classes (in color) from nude and draped models" (Washington University Archives, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri).

2. "Nude" was exhibited at the Salon of the Société des Artistes Français in Paris in May 1912. In the United States it was exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1912-13; the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, 1913; the National Academy of Design, New York, winter 1913-14; and the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco, 1915. An article, "Chicago Shocked! Who Did the Deed?" in an unidentified newspaper, dated November 7, 1914, gives an account of the controversy surrounding the painting during its exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago's "Twenty-seventh Annual Exhibition of American Oil Paintings and Sculpture," November-December 1914 (Artist File, Saint Louis Art Museum Library).

3. "Nude" was purchased from the artist on March 4, 1917, by Des Moines contractor and collector James S. Carpenter, on behalf of the Des Moines Association of Fine Arts, which he founded. Letters to Mr. Carpenter (solicited by him) from various art world professionals, artists, dealers, a museum director, written in April 1917 recommending the painting to him highly, would indicate that such support was deemed necessary in persuading the association's board of the work's merit. Sometime after its acquisition it was entitled "The Jewel Box", a further attempt, one suspects, to lessen the impact of the subject (Painting Files, Des Moines Art Center, Iowa).

4. Miller's close friend and colleague Frederick Frieseke chose to remain in France in part because he felt more free to paint the nude there (Clara T. MacChesney, "Frieseke Tells Some of the Secrets of His Art," New York Times, June 7, 1914, p. 7).

5. The painting entered the collection of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, in 1920, acquired as a gift. Its present location is unknown.

6. A photograph of Miller's Paris studio in the early 1900s shows a Japanese print hanging on the wall (Family scrapbook). Japanese prints also hung in his Provincetown home (photographs, Mildred Carpenter, 1931; Saint Louis Art Museum, Archives).

7. "Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design 9" (July 1921): cover, 26.

8. In a 1937 newspaper interview ("R. E. Miller, Noted Artist, Comes Home for Christmas Holiday," Globe-Democrat, December 9, 1937 [Artist File, Saint Louis Public Library]), Miller is described as doing his "money-making painting" during the summer, thus having the rest of the year to paint, in his words, "what and as I please."

9. For a full discussion of this subject see William H. Gerdts, "The Great American Nude: A History in Art", exhib. cat. (New York: Praeger, 1974). See also Ada Rainey, "Corcoran American Exhibition," "Washington Post", October 28, 1928, p. 10; she remarks that the large number of figure paintings in the exhibition is "a new trend."

10. Leila Mechlin, "Life and Unrest of the Day Reflected in Paintings," Washington Sunday Star, March 26, 1939 (scrapbooks, Archives, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.).

11. An influential teacher (later director) at the Washington University School of Fine Arts during Miller's student years was Edmund H. Wuerpel, a close friend of Whistler's and a strong admirer of his work.

12. Quoted in Thompson, "Richard Miller," p. 711.

13. For Miller, the way a painting was structured was of paramount importance. In 1932 he told a newspaper reporter, "Atmosphere and color are never permanent. Paint won't remain the same color forever. But the design will stay. And that is the creative part of it. The rest, after all, is a sort of copying." ("Modernism Fast Growing Old-Fashioned, Artist Says," Post-Dispatch, December 27, 1932 [Artist File, Saint Louis Public Library]).

On View

Not on viewCollections