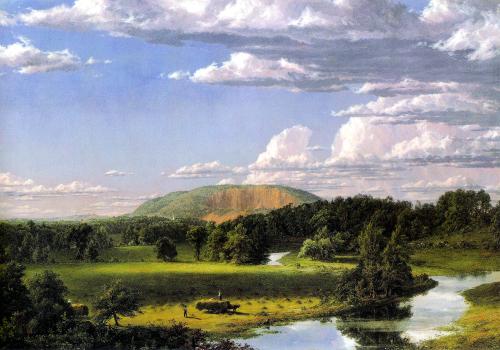

West Rock, New Haven

West Rock, New Haven

Artist

Frederic Edwin Church

American, 1826 - 1900

Date1849

MediumOil on canvas

Dimensions27 1/8 × 40 1/8 in. (68.9 × 101.9 cm)

Frame: 40 7/8 × 54 × 5 in. (103.8 × 137.2 × 12.7 cm)

Frame: 40 7/8 × 54 × 5 in. (103.8 × 137.2 × 12.7 cm)

Credit LineJohn Butler Talcott Fund

Object number1950.10

On View

On viewCollections

- Connecticut Landscape

- Exploring the Seasons: School Tour

- 19th Century Landscapes and the Hudson River School

- Math-terpieces: School Tour

- What is America?: School Tour

Related