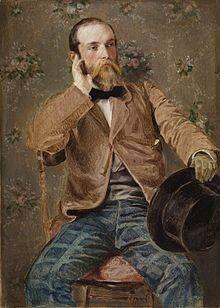

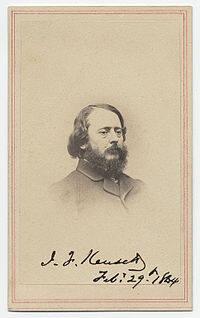

Eastman Johnson

American, 1824 - 1906

Birth-PlaceLovell, ME

Death-PlaceNew York, NY

BiographyJonathan Eastman Johnson (1824-1906)Eastman Johnson was born in Lovell, Maine, and began his career in Boston in 1840 as an apprentice in Bufford’s Lithographic Shop, designing title pages for books and sheet music. He became an itinerant portrait painter in 1842, and for the next seven years he worked in Newport; Portland, Maine; Washington, D.C.; and Boston. In 1849 Johnson traveled to Germany, where he studied at the Düsseldorf Academy, and joined the studio of Emanuel Leutze, who was then working on the second version of his “Washington Crossing the Delaware” (1851; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Johnson continued his studies in The Hague, where he spent three and a half years studying the painterly brushwork of the seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish masters, and in 1855 he enrolled in the Paris studio of Thomas Couture.

Settling in New York in 1858, Johnson opened a studio in the University Building and began work on “Negro Life at the South” (1859; New-York Historical Society), which he exhibited at the National Academy of Design to the acclaim of abolitionists and slaveholders alike. The following years were devoted to Civil War subjects and to the traditional American genre scenes for which he became best known. During the 1860s he began a series of maple-sugaring scenes in Maine and bought his first property on Nantucket in 1871. He was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design in 1859 and became a full member in 1860. Johnson became prominent in New York art circles, joining the Century Association and the Union League Club and becoming a founding trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the 1880s Johnson began to refocus his attention on portraiture, dedicating the last two decades of his career to the depiction of the nineteenth century’s wealthy industrialist class.

Hollyhocks, 1876

Oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 30 1/2 in. (60.3 x 77.5 cm)

Signed and dated (lower left): E. Johnson 1876

Harriet Russell Stanley Fund (1946.7)

“Hollyhocks” depicts nine young women enjoying a summer afternoon in a garden. They quietly tend the blooming hollyhock plants or casually converse beneath a vine-laden arbor. Their elegant attire and their pretty unlined faces attest to an existence free from the trials of hard work. Refined outdoor activities became an accepted form of leisure after the Civil War, and with the increased industrialization of the late nineteenth century such paintings of pastoral bliss became popular among the newly urbanized elite.

Johnson executed “Hollyhocks” following extensive training in Europe, and the influence of his teacher Thomas Couture is especially evident in the fluid application of color and in the academic method of building up the composition from a series of individual studies. Johnson exhibited one of these studies, “Catching the Bee” (1872; Newark Museum, N.J.) at the National Academy of Design in New York in 1872. This highly finished work shows young woman plucking a single blossom from the tall stem of a hollyhock plant. Four years later Johnson incorporated this figure into the left side of “Hollyhocks”. “Catching the Bee” and “Hollyhocks” display a brighter palette and stronger contrasts of light and shadow than Johnson’s paintings of the previous decade, revealing the artist’s exploration of natural light in the 1870s.

The subject of women in an enclosed garden has a long tradition in art history. The enclosed garden, or hortus conclusus, was traditionally associated with the Garden of Eden, a theme with potent implications for artists of the New World. It was also identified with the purity of the Virgin Mary, and many late-nineteenth-century artists extended this analogy to women in general. An evocative floral language developed to suggest the fertility and beauty of the female sex. In “Hollyhocks” the flowers stand as tall as the women, their lyrical swaying attitudes mirroring the grace of their human counterparts.(1) The women, like the hollyhocks, are arranged decoratively along the periphery of the compound, and the red, pink, and white of their gowns are the colors of hollyhock blooms. Enclosing the hollyhocks--and, by extension, the nineteenth-century women--within the confines of a walled garden allowed them the benefits of air and light without exposing them to the dangers of the rapidly modernizing world. From this sheltered position, both the women and the flowers in “Hollyhocks” become beautiful, but passive, objects of contemplation.

MEB

Bibliography:

John I. H. Baur, “An American Genre Painter: Eastman Johnson”, 1824-1906, exhib. cat. (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, 1940); Patricia Hills, Eastman Johnson, exhib. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1972); Patricia Hills, “The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes” (New York: Garland, 1977); Marc Simpson, Sally Mills, and Patricia Hills, “Eastman Johnson: The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket”, exhib. cat. (San Diego: Timken Art Gallery, 1990).

Notes:

. Annette Stott, "Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition," “American Art” 6 (spring 1992): 69.

Person Type(not assigned)