Sam Francis

1923 - 1994

Death-PlaceSanta Monica, CA

Birth-PlaceSan Mateo, CA

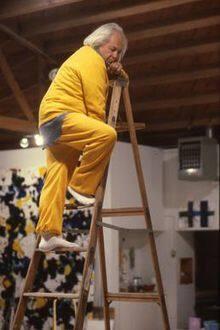

BiographySam Francis (1923-1994)Sam Francis was born in San Mateo, California. His father was a mathematics professor and his mother was an accomplished pianist who died when Francis was twelve. In 1941 he entered the University of California at Berkeley, where he studied psychology and medicine. While serving in the United States Army Air Corps in 1943-44, he had a flying accident that aggravated his spinal tuberculosis. While in the hospital, he began to paint. In 1948 he was well enough to return to Berkeley and received a B.A.(1949) and an M.A.(1950) in art and art history. While his first paintings were inspired by the Surrealists, his work at Berkeley was influenced by the emerging Abstract Expressionists Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock.

In 1950 Francis moved to Paris, where he studied briefly at the Académie Fernand Leger and met the Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle, who remained an important influence. His first one-man exhibition was in 1952 at the Galerie du Dragon, where he showed large muted monochromatic oils composed of transparent and dripping layers of color. Exposure to the work of Bonnard, Matisse, and Monet reinforced Francis's preference for light and often intense, vibrant color. In 1953 Michel Tapie included Francis's work in the exhibition "Un Art Autre" at Studio Paul Facchetti, Paris, which identified a European form of Abstract Expressionism called Tachisme. In 1956 he had his first one-man exhibition in New York, at the Martha Jackson Gallery.

An extended visit to Japan in 1957 during a trip around the world coincided with Francis's strikingly bold use of white space and increasingly asymmetrical compositions, a process of opening up empty space within the field of color cells that he had begun in late 1955. Three large-scale mural projects occupied him at this time: for the Basel Kunsthalle (1956-58); for the auditorium in the Sogetsu School of the sculptor and flower arranger Sofu Teshigahara in Tokyo (1957); and for the Chase Manhattan Bank in New York (1959). In 1959 Francis married Teruko Yokoi. A recurrence of his tuberculosis led to a ten-month hospitalization in Bern in 1961. He returned to Santa Monica in 1962, and he and his wife were divorced the following year.

Reflecting his involvement with lithography and his use of acrylic paints, Francis's colors become less modulated, bright, hard, and cold. In 1964 he was included in Clement Greenberg's landmark exhibition "Post-Painterly Abstraction" at the Los Angeles County Museumn of Art, but, as always, Francis was wary of being closely tied to any art movement. He bought a home in Santa Monica in 1965 and maintained studios in Paris, Tokyo, and Bern. In 1965 he married Mako Idemitsu, and they established a residence in Tokyo in 1966. In the late 1960s his work became more austere, silent, focused on the white empty spaces of his compositions, with color streamers placed at the periphery.

In 1971 Francis began work with a Jungian analyst in Los Angeles, which marked the beginning of his ongoing involvement with Jungian psychology and with alchemy, especially as it related to printmaking. Even within the context of the 1960s renaissance of printmaking, Francis's commitment to the medium was unusual. In 1970 he established the Litho Shop in Santa Monica, which also managed his exhibitions and archives. Throughout the 1970s he worked at Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, making lithographs and screenprints. In 1975 he started making monoprints; in 1981 he made a long-term commitment to etching.

Francis's preoccupation with the void gave way in his prints to a series of self-portraits (ca. 1973), mandala forms (ca. 1975), and spattered grids (late 1970s). In the 1980s his grids loosened up to letter or snakelike configurations covered with web like arabesques and brilliantly colored drips. From the late 1980s until his death, Francis continued his celebration of sensuous color and light with explosive energy.

Yielding, 1982

Acrylic on paper, 37 x 71 3/4 in. (94 x 182.2 cm)

Alix W. Stanley Fund (1983.54)

“Yielding” engages the viewer in looking for order beneath the seeming chaos of corpuscular color balls within an abstract pictorial field, a process that involves the viewer with Francis's way of making forms, of differentiating and ordering the application of color. Two paintings, “Simplicity” (1980; Saison Foundation, Tokyo) and “The Bound and the Unbound” (1984; estate of the artist), provide a historical framework for the dialogue of order and chaos found in “Yielding”.(1)

“Simplicity” represents a culminating moment in Francis's oeuvre. Having replaced the white void of his paintings of the late 1960s with the strongly centered mandala structure of the paintings, lithographs, and monotypes of the mid-1970s, Francis sought greater looseness: centralized structure yielded to the uncentered grid, which supports an ever more spontaneous play of light-filled color. One of his aphorisms published in 1975 speaks to this process: "He is named space / He is named time / He is named light / He is named / He has the mercy of eternity / He is spreading / (moving in space is spreading) / moving is possible / because of easing / because of loosening."(2)

In the early 1980s Francis returned to the problem of how to reconcile structure and spontaneity. As structure became more dynamic, it allowed for greater spontaneity. The very title “The Bound and the Unbound” points to the concern that led him to push his art toward an ever greater loosening. Francis's explorations in the medium of etching were especially important in this evolution. In works from 1981, such as “Totem”, “Second Mother”, and “First Subject” (all National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), strong diagonals play an important role. Their dynamism enters into a dialogue with the fluid, spatially subtle properties of etching.(3) The excitement of this dialogue is brought, at a larger scale and in a more unusual medium for Francis, to “Yielding”, an acrylic on paper. Although technically a drawing, “Yielding” visually and viscerally functions very much like a painting.

Beneath the seeming chaos of corpuscular balls of colored matter (thick, matte, sometimes "cratered," largely red, though often paired with turquoise balls), one immediately notices the structuring order of a white bar separating sloping beams. This structure acts as a magnet, beginning to organize and interact with the color balls: the fuchsia ball in the lower right corner, juxtaposed with a blood red ball to its left, marks the origin of the lower wider beam. Red balls float at pictorially strategic points: at the top center of the beam, above the joining of the leglike struts that help support its diagonal rise, and between these struts in conjunction with turqoise.

Another such pairing of red and turquoise occurs in the center of the pictorial field, where the turquoise takes the eye and the imagination into the white bar; its quality as a spatial void recalls Francis's preoccupation with the void in the late 1960s. While the bottom beam is characterized by mottles and specks that recall the Milky Way, the narrower, less clearly defined beam above this bar is a massing of substantial color balls, especially in the juxtaposition of red, turquoise, and dark blue just to left of center. This massing establishes a directional force, taking the eye farther toward the upper left, where a gestural trajectory of dark blue opens into action and a new space; a different kind of action than the diagonal trajectories of the beams, a different kind of space than the Milky Way of the lower beam or the denser constellations of the upper beam. This looping space of a gesture continues, in a second swing,in red.

The red gesture loops up onto the organic folds of the red area that holds the upper left hand corner, reminding us of the work's modernist pictorial surface. The other corners are also pinned by red: an architectural slab of boldly brushed-on red in the lower left, the matte diagonally brushed triangular tab in the upper right. This focus on binding corners brings us back to the fuchsia ball in the lower right: we begin to appreciate its contribution to the loosening of this pictorial universe. As we continue to explore complexities, discovering new points of order, we remain tantalized by the chaotic elements that give “Yielding” an unending life.

ELL

Bibliography:

Robert T. Buck, Franz Meyer, and Wieland Schmied, “Sam Francis: Paintings”, 1947-1972, exhib. cat. (Buffalo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1972); Peter Selz, “Sam Francis” (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1975); Connie W. Lembark, “The Prints of Sam Francis: A Catalogue Raisonné”, 1960-1990, 2 vols. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1992); Pontus Hulten, “Sam Francis” (Stuttgart: Edition Cantz, 1993).

NOTES:

1. Pontus Hulten posits order/chaos as a framework for appreciating Francis's art (Sam Francis, p. 17).

2. Quoted in ibid., p. 37.

3. On the structural dynamism of etchings, see Ruth E. Fine, "Patterns across the Membrane of the Mind," in Lembark, Prints, vol. I, p. 30. On Francis's concentration on the fluid, broadly drawn, tonal variations possible with sugar-life and spitbite aquatint, see ibid., pp. 20, 30.

Person Type(not assigned)