N.C. Wyeth

American, 1882 - 1945

Death-PlaceChadds Ford, PA

Birth-PlaceNeedham, MA

BiographyNewell Convers Wyeth (1882-1945)

N. C. Wyeth was born on a farm in the rural town of Needham, Massachusetts. Throughout his life, he drew upon his memories of farming techniques, horse accoutrements, and the expressive movements of farmhands doing their chores. Wyeth's training as an artist began at the Massachusetts Normal School about 1899. In 1901 he moved on to the Eric Pape School of Art in Boston and the next year to the Howard Pyle School of Art in Wilmington, Delaware. The months at Pyle's school were important not only for Wyeth's training as an artist but also for the history of illustration in this country, as the mantle of preeminent American illustrator was passed from teacher to student.

Wyeth published his first illustration while at Pyle's school. In 1903 the “Saturday Evening Post” paid him fifty dollars for a painting of a cowboy riding a bucking bronco, which appeared on the cover of the February issue. In 1904 the magazine and the publisher Scribner's sent Wyeth out West to document a lifestyle that seemed exotic to the urban readership of the East Coast. The artist sent back paintings of western life accompanied by firsthand accounts of his adventures. These articles were very popular and established Wyeth as an important illustrator.

Wyeth’s illustrations for a 1911 edition of Robert Louis Stevenson's “Treasure Island” were a huge success and led to illustrations for Stevenson's “Kidnapped” (1913), Mark Twain's “Mysterious Stranger” (1916), and many other adventure tales. Wyeth's illustrations for James Fenimore Cooper's “The Last of the Mohicans” (1919) and “The Deerslayer” (1925) were important as well. As he continued to illustrate classic novels, Wyeth also occupied himself making paintings for advertisements, posters, magazines, newspapers, and murals.

In the last years of his life, Wyeth turned down more assignments than he accepted and concentrated on painting subjects of his own choosing, mainly scenes set around Chadds Ford, where he had spent most of his life. He was killed when his car collided with a train in 1945.

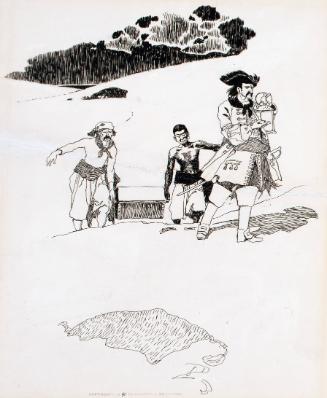

"One More Step, Mr. Hands," Said I, "And I'll Blow Your Brains Out" (Israel Hands; One More Step, Mr. Hands), 1911

Oil on canvas, 47 x 38 3/8 in. (119.4 x 97.5 cm)

Signed (lower right): N. C. WYETH

Harriet Russell Stanley Fund (1953.18)

The narrative depicted in this painting takes place after Jim Hawkins, the young hero of “Treasure Island”, boards a foundering schooner called the “Hispaniola”. The ship has been taken over by a mutinous crew and is sailing aimlessly with only two ailing mates onboard. One of the mutineers, Israel Hands, concocts a scheme to take the helm from Hawkins. The dénouement, as shown in the painting, occurs when Hawkins gains an advantage over Hands and blasts him into the waters surrounding Treasure Island.

Wyeth painted in a traditional style that can be linked to Titian and Rembrandt. These artists began with an underpainting in earth tones and built up the color while allowing the first coat to come through to warm up the cool blues and greens. In “One More Step, Mr. Hands” this technique imbues the tropical seascape with a hazy, humid atmosphere. The composition replicates the tension of the dramatic moment in the story. The shrouds, mast, and other rigging on the schooner act as diagonal elements to point the viewer toward the central figure of Jim Hawkins. Israel Hands’s outstretched arms at the bottom of the picture lead the eye from the extreme foreground toward the center of the composition. Andrew Wyeth, N. C. Wyeth’s son, observed that his father’s special talent was depicting high drama: "Look at the picture of Jim Hawkins in the crow's- nest, and you can see how he worked toward something like angle shots in motion pictures. Much as a camera does, you zoom in on things." (1) The loose handling of the paint also enhances the sense of movement. The foreground figure of Israel Hands in the act of throwing his dirk toward Hawkins is executed very quickly with bravura slashes of paint, while the motionless figure on the mast is silhouetted and painted in a more static way, befitting the narrative. Both figures were composed freely, without the use of models, as Wyeth preferred.

The version of “Treasure Island” for which Wyeth did seventeen paintings in color, (2) including cover, endpapers, and title page, was not the first printing of this book; the first edition, published in 1883, had no illustrations. A sickly man for most of his life, Stevenson did not live to see Wyeth's work; he died in 1894 at the age of forty-four in Samoa.

MRS

Bibliography:

Betsy James Wyeth, ed., “The Wyeths: The Letters of N. C. Wyeth, 1901-1945” (Boston: Gambit, 1971); Douglas Allen and Douglas Allen Jr., “N. C. Wyeth: The Collected Paintings, Illustrations, and Murals” (New York: Crown, 1972); James H. Duff, “Not for Publication: Landscapes, Still Lifes, and Portraits by N. C. Wyeth”, exhib. cat. (Chadds Ford, Pa.: Brandywine River Museum, 1982); James H. Duff et al., “An American Vision: Three Generations of Wyeth Art”, exhib. cat. (Chadds Ford, Pa.: Brandywine River Museum, 1987).

Notes:

1. “Painting: Aloft with Hawkins,” “Time 88” (August 26, 1966): 63.

2.. Robert Louis Stevenson, “Treasure Island” (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911).

Person Type(not assigned)