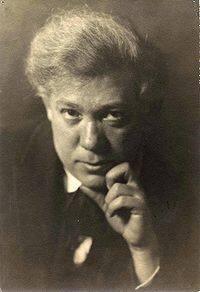

Abraham Walkowitz

1880 - 1965

Death-PlaceBrooklyn, NY

Birth-PlaceSiberia, Russia

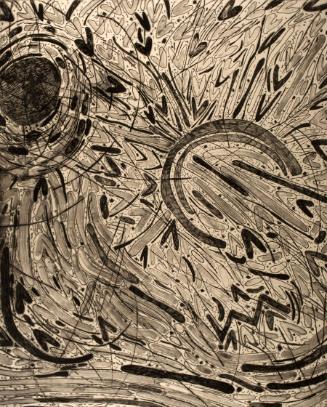

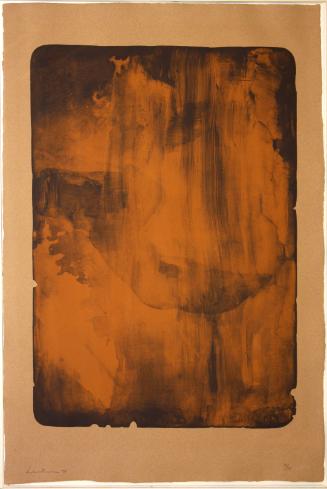

BiographyOriginally from Russia, Walkowitz moved to America at a young age. He first studied at the National Academy of Design in New York, and later at the Académie Julian in Paris. Upon his return from studying abroad, Walkowitz was known as one of the "Early American Moderns." He was completely liberated from tradition and painted in various styles including Cubism, Futurism, nonobjective watercolors, and linear motion studies. EXTENDED BIO

Abraham Walkowitz (March 28, 1878 - January 27, 1965) was an American painter grouped in with early American Modernists working in the Modernist style. Walkowitz was born in Tyumen, Siberia to Jewish parents. He emigrated with his mother to the United States in his early childhood. He studied at the National Academy of Design in New York City and the Académie Julian in Paris under Jean-Paul Laurens. Walkowitz and his contemporaries later gravitated around photographer Alfred Stieglitz's 291 Gallery, originally titled the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, where the forerunners of modern art in America gathered and where many European artists were first exhibited in the United States. During the 291 years, Walkowitz worked closely with Stieglitz as well as Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin (often referred to as "The Stieglitz Quartet"). Walkowitz was drawn to art from childhood. In a 1958 oral interview with Abram Lerner, he recalled: "When I was a kid, about five years old, I used to draw with chalk, all over the floors and everything... I suppose it's in me. I remember myself as a little boy, of three or four, taking chalk and made drawings."[1] In early adulthood, he worked as a sign painter and began making sketches of immigrants in New York's Jewish ghetto where he lived with his mother. He continued to pursue his formal training, and with funds from a friend traveled to Europe in 1906 to attend the Académie Julian. Through introductions made by Max Weber, it was here that he met Isadora Duncan in Auguste Rodin's studio, the modern American dancer who had captured the attention of the avant-garde. Walkowitz went on to produce more than 5,000 drawings of Duncan.

Walkowitz' approach to art during these years stemmed from European modernist ideas of abstraction, which were slowly infiltrating the American art psyche at the turn of the century. Like so many artists of the time, Walkowitz was profoundly influenced by the 1907 memorial exhibition of Cézanne's work in Paris at the Salon d'Automne. Artist Alfred Werner recalled that Walkowitz found Cézanne's pictures to be "simple and intensely human experiences."[2] Working alongside other Stieglitz-supported American modernists, Walkowitz refined his style as an artist and produced various abstract works.

Times Square, 1910

Although Walkowitz drew influences from modern European masters, he was cautious not to be imitative. Artist and critic Oscar Bluemner recognized this quality in Walkowitz’s work, citing the differences between the highly influential writings of Kandinsky and Walkowitz' style. He wrote: "Walkowitz is impelled by the ‘inner necessity’: Kandinsky, however, like the other radicals, appears not to proceed gradually and inwardly, but with a mind made up to commit an intellectual feat—which is not art."[3]

Walkowitz first exhibited at the 291 in 1911 after being introduced to Stieglitz through Hartley, and stayed with the gallery until 1917. During the 291 years, the climate for modern art in America was harsh. Until the pivotal Armory Show of 1913 had occurred which Walkowitz was involved with and exhibited in, modern artists importing radical ideas from Europe were received with hostile criticism and a lack of patronage. While never attaining the same level of fame as his contemporaries, Walkowitz' close relationship with the 291 Gallery and Alfred Stieglitz placed him at the center of the modernist movement. His early abstract cityscapes and collection of over 5,000 drawings of Isadora Duncan also remain significant art historical records.

REFERENCES

Lerner, Abram, and Bartlett Cowdrey. "Oral History Interview With Abraham Walkowitz." 8 Dec. & 22 Dec. 1958. Smithsonian Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/walkow58.htm

Jump up ^ Alfred Werner, "Abraham Walkowitz Rediscovered," American Artist (August 1979): 54-59, 82-83.

Jump up ^ Oscar Bluemner, "Walkowitz," 1933, reprinted in A Demonstration of Objective, Abstract, and Non-Objective Art, 4.

^ Jump up to: a b Sheldon Cheney, The Art of the Dance: Isadora Duncan, (New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1969), 47.

Jump up ^ Isadora Duncan, My Life (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 1927), 75.

Jump up ^ Walter Terry, Isadora Duncan: Her Life, Her Art, Her Legacy (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1963), 115.

Jump up ^ Abraham Walkowitz, "Foreword," 1913, reprinted in A Demonstration of Objective, Abstract, and Non-Objective Art, 2.

Jump up ^ "Oral History Interview."

Person Type(not assigned)