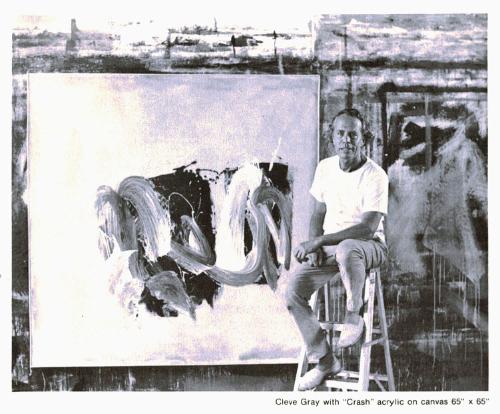

Cleve Gray

1918 - 2004

Birth-PlaceNew York, NY

Death-PlaceHartford, CT

BiographyCleve Gray (b. 1918)A native New Yorker, Cleve Gray attended the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, from 1934 to 1936 and graduated from Princeton University in 1940. His senior thesis was on Chinese Yuan-dynasty landscape painting, which marked the beginning of a lifelong interest in Asian art and philosophy. After serving in the army during World War II, Gray studied painting with Andre Lhote in Paris becoming the close friend and unofficial disciple of Jacques Villon, a brother of Marcel Duchamp. The experience of the war provoked a series of paintings on London ruins and the Holocaust, exhibited in Gray's first one-man show, at the Jacques Seligmann Gallery in New York in 1947. In 1949 he exchanged frenetic New York for the farmland of Warren, Connecticut, where he has lived and worked ever since, except for regular and extensive travel abroad.

In the late 1940s Gray tried to infuse imaginative content into the School of Paris style; however his reputation as an aspiring School of Paris master, just as the avant-garde Abstract Expressionists were "sweating out Cubism," was damaging. While he had reservations about Abstract Expressionism's nonobjective basis and what he perceived as its lack of structure, his friendship with many of its leading practitioners, such as Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, David Smith, and Tony Smith, did influence the evolution of his own art, which, from the late 1950s through the 1960s moved toward greater abstraction, simplification, gestural emphasis, and more vivid color.

Like the Abstract Expressionists, Gray put his trust in the spontaneous, but consulted his own sources, especially Asian calligraphy. In 1963 he discovered the power of direct gesture, but it was a trip to Greece in 1964 that led him to probe the psychological and spiritual possibilities of abstract art. There, he discovered a vertical image--for him, part goddess, part column, part tree--that would occupy him for the next ten years. He started his characteristic method of working in series, variations on a theme, in search of its essential core. In 1957 Gray had married writer Francine du Plessix Gray, stepdaughter of Alexander Liberman. Their first child was born in 1959, precipitating a pregnancy sculpture that already hints at the "vertical theme," which he was to pursue more rigorously, in, for example, the series Ceres of 1967.

The Vietnam war also had an impact on Gray’s artistic evolution. He and his wife devoted more and more time to anti-war activities, founding the northwest Connecticut chapter of Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam, protesting and being jailed in 1970. These efforts exacerbated his sense of abstract art's separation from a public social function. In the late 1960s writing became more important to Gray who had been a contributing editor to “Art in America” since 1960.

As an artist-in-residence at Honolulu Academy of Art in fall 1970, Gray painted a Hawaiian series in response to the lush landscape. The following spring he produced a series of bronze sculptures inspired by the Kilanea lava flow. During a visit to Spain in fall 1971 he continued his exploration of the vertical theme in the “Sheba” series (1971-72). For the Theater Gallery of the Neuberger Museum at Purchase, New York, Gray created a sequence of fourteen monumental paintings entitled “Threnody”, from the Greek for a song or lamentation for the dead (1972-73), bringing both the vertical theme and his sense of the tragedy of the Vietnam war to an acclaimed, culminating expression.

Gray opened up a new direction in his art in the “Triptychs” series (1974), which shows his renewed interest in calligraphic line and the challenge of "the void" of the color field. In the “After Jerusalem” series (1975), he found inspiration, once again, in the techniques of Asian calligraphy. At the American Academy in Rome in 1979 and again in 1980, he worked on the “Roman Wall” series in which such Chinese properties as "the power of empty space," "symmetries," and "fluidity of focus”, to use Gray's words, come into play. Visiting Japan in 1982, he traveled to Kyoto where he studied the gardens that inspired his “Zen Gardens” series that anticipated his “In Prague—1984” series inspired by the old Jewish cemetery.

The human figure, last seen in Gray's late Cubist work of 1963, reemerges in the “Holocaust” series (1985) and the “Resurrection” series (1986). The new dialogue between figuration and abstraction also animates “Four Heads of Anton Bruckner” (1987). In 1988, in response to his long-standing interest in public art, Gray was awarded the commission for a 635-foot mural in porcelain enamel tile for the façade of the Union Train Station in Hartford, Connecticut. In 1989, after a period of poor health, he produced a series of abstract paintings entitled “The Lovers, The Edge, The Broken Horizon”, in which he presented three variations on a long-sought-for synthesis of painting and drawing. Much as the experience of the Greek landscape had first led him to probe the expressive possibilities of abstract art, Aeschylus's play inspired Gray in his series “The Eumenides” (1994) to use his now fully mature and articulate pictorial language in a meditation on the transformation of the horrifying Furies into the benevolent Eumenides.

Bibliography:

Thomas B. Hess, “Cleve Gray: Paintings”, 1966-1977, exhib. cat. (Buffalo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1977); Carter Ratcliff, “Cleve Gray: In Prague—1984”, exhib. cat. (New York: Armstrong Gallery, 1984); Linda Konheim Kramer, “Cleve Gray: Works on Paper, 1940-86”, exhib. cat. (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 1986); Charlotta Kotik, “Cleve Gray: The Painted Line”, exhib. cat. (New York: Berry-Hill Galleries, 1990); Patrick McCaughey, “Cleve Gray: Romantic/Modern”, exhib. cat. (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1994); Barbara Rose, “Cleve Gray: The Art of Memory/ Threnody, Zen Gardens, Prague Cemeteries”, exhib. cat. (Purchase, N.Y.: Neuberger Museum of Art, 1996).

“Zen Gardens #36”, 1982

Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 70 in. (152.4 x 177.8 cm)

Signed, dated, and inscribed (verso): “Gray--82 Zen Gardens #36 acrylic 60 x 70”

Friends Purchase Fund and Gift of Artist (1987.20)

Barbara Rose credits Cleve Gray with the distillation, after many years of study, self-analysis, travel, and experience, of "a personal style that is recognizable in its mastery and fusion of the two great traditions of the civilized world, the Western European and that of the ancient cultures of China and the Far East."(1) The “Zen Gardens” series of 1982-83 marks an important point in their fusion and “Zen Gardens #36”, a turning point within the series.

Gray's involvement with Eastern philosophy and art preceded his knowledge of Cubism and the advanced styles of the West. Throughout its long history, Chinese landscape art, both painting and gardening, has sought to represent the ideal harmony of yin and yang, the two great opposing forces that in Chinese philosophy are held to animate the universe and the constant change within it. Japanese Zen gardens are themselves distillations of the harmony of yin and yang; indeed, their miniature landscapes are often based on Chinese, not Japanese, countryside and landscape paintings.(2) These gardens became one of the great Japanese Buddhist arts in the thirteenth century when Zen sects began to use them as an aid to contemplation. Since Zen understood enlightenment as a direct experience of the "here and now" brought about through meditation, Zen artists largely dispensed with the elaborate pantheon of Buddhism and concentrated on trying to capture the essence or spirit of things. In painting, a single brushstroke could represent a massive mountain or the beak of a sparrow. In landscape gardening, the search for the essential reached the conclusion found at Ryoanji, where trees, bushes, and water have been omitted entirely, leaving only fifteen stones, sand, and moss to suggest a great landscape. The "opening and closing" relationships of rocks and pebbles, of mountain and sea, of negative and positive shapes, solids and voids, horizontal and vertical were invoked as evidence of balanced yin and yang.(3)

When Gray was in Japan in 1982, he spent ten days in Kyoto looking at four or five Zen gardens a day. The power of Asian art and philosophy that had absorbed him as a student was now concretized and renewed. "I love the ambivalence of the Zen gardens," he stated. "If you close your eyes and think about it, the relationship between the rocks was in continual movement, the rhythms were never static rhythms, although the rocks were static. I love that yin-yang relationship."(4) This experience in Japan precipitated the “Zen Gardens” series, the most extensive pictorial exploration of one subject that Gray has ever undertaken.

The initial idea for the series came to Gray during the plane ride home: to render the rocks in color, in different hues, but muted by a white transparency on top of the color, then to have a black line that would not outline as much as emphasize the rhythm of the rocks and the relationships between them. The first four paintings in the series were executed in this manner--a calligraphic response to muted color. In the second phase of the series, the colors gradually intensified to the high pitch seen in “Zen Gardens #36”. There, the four rock shapes are a mustard yellow, a hot orange, a light turquoise, and a darker purplish blue. To the right is the rectilinear matte gray "path" traversing the right-hand surface of the canvas, the "path" emblematic of the human presence deemed necessary in traditional Asian landscape art to signal a universal harmony, inclusive of heaven, earth, and man.(5) A calligraphic black line, created by the drag of a dry brush, mounts the path to a circular point that is echoed in the bigger black circle at the bottom, from which seem to emanate a dozen or so black calligraphic gestures that explore, probe, or sweep by the color "rock shapes," acknowledging their juncture points, meditating on their colored substance.

The calligraphic gesture is, of course, central to the Eastern tradition. Gray pointed "to the vexing problem of the painted line, a problem which has preoccupied and tantalized me for many years. This is a concern fraught with the difficulty of making line resolute, energetic, expressive, ever involved with line's relation to the void and to the potential inspiration it may find in Oriental calligraphy."(6) He was, as he put it, in search of "a structure that would be the linear configuration itself. A configuration that would exist in a void, in a relationship that would express a harmony of opposites."(7) While Gray's gestural spontaneity did grow to entertain color in the Roman Wall series in 1979-80, he retrenched in the “Zen” series of 1981, just prior to the “Zen Gardens” series, into an almost colorless calligraphy, working with bamboo, India ink, and acrylic on paper. This position in his exploration of calligraphic line perhaps accounts for the initial idea in the “Zen Gardens” series of muting the colored rocks with an enveloping white transparency.

The degree to which color began to assert itself in the second phase of the series took Gray by surprise. "I wanted to try and represent the rocks by something opposite from the way it was naturally, and that was part of the ambivalence I liked," he explained. "The shape was so much the shape of the rocks that I wanted to reverse my tendency towards the realism by some totally different approach to the same thing." Color was a marvelous way to generate the spatial sensations and relations so central to the experience of the Zen garden. Here, his chosen medium of acrylic comes into its own. Gray observed how the ground color comes through the other colors as they are applied: "Transparency is what I love in using acrylic. If it gets opaque then generally I destroy the painting." Note the resulting subtleties of spatial differentiation in “Zen Gardens #36”, the shifts between the dark and turquoise blues, the juncture of turquoise and hot orange, the hot orange overlapping the mustard yellow, and the varying qualities of gestural application visible even within the colored areas themselves--for instance, the heightened gestural vibrancy within the central turquoise.

Such subtleties elicit yet further subtleties in the spatial voyage of the calligraphic gestures, their thickening and thinning, their speed and points of homecoming and recognition of the positions, relations, and qualities of the colored substances. Sometimes, to heighten the spontaneity of the calligraphic response, Gray even closed his eyes when making his gestures, a risky process that sometimes forced him to sponge out a mark, possible in the acrylic medium. Thus he brought the dialogue of intense vibrant color areas and spontaneous calligraphic line to a high pitch in “Zen Gardens #36”. What was only a schematic colorless presentation of the challenges of the dynamism of yin and yang in the circular "cosmic" gestures of the After “Jerusalem” series of 1975 had now blossomed into a full differentiation and articulation of his pictorial means, as he orchestrated the continuing circulation of the viewer's attention between the calligraphic energies and their meditative interchange with the colored rocks.

ELL

Bibliography:

Thomas B. Hess, “Cleve Gray: Paintings”, 1966-1977, exhib. cat. (Buffalo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1977); Carter Ratcliff, “Cleve Gray: In Prague—1984”, exhib. cat. (New York: Armstrong Gallery, 1984); Linda Konheim Kramer, “Cleve Gray: Works on Paper, 1940-86”, exhib. cat. (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 1986); Charlotta Kotik, “Cleve Gray: The Painted Line”, exhib. cat. (New York: Berry-Hill Galleries, 1990); Patrick McCaughey, “Cleve Gray: Romantic/Modern”, exhib. cat. (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1994); Barbara Rose, “Cleve Gray: The Art of Memory/ Threnody, Zen Gardens, Prague Cemeteries”, exhib. cat. (Purchase, N.Y.: Neuberger Museum of Art, 1996).

Notes:

. Rose, “Cleve Gray”, n.p.

2. Mitchell Bring and Josse Wayembergh, “Japanese Gardens: Design and Meaning” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981), p. 173.

3. Ibid., pp. 153, 186.

4. Unless otherwise stated, all quotes by Gray are taken from author's taped interview with the artist, Warren, Connecticut, November 21, 1996.

5. Bring and Wayembergh, “Japanese Gardens”, p. 153.

6. Cleve Gray, "Artist's Statement," in Kotik, “Cleve Gray”, n.p.

7. Gray, unpublished biographical ms., Albright-Knox Art Gallery files, as cited in Hesse, “Cleve Gray”, p. 59.

Person Type(not assigned)