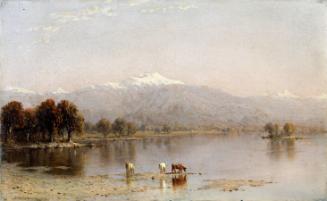

Sunday Morning

Artist

Asher Brown Durand

American, 1796 - 1886

Date1860

MediumOil on canvas on wood paneled stretcher

Dimensions28 1/8 × 42 1/8 in. (71.5 × 107 cm)

Frame: 39 × 53 × 4 3/4 in. (99.1 × 134.6 × 12.1 cm)

Frame: 39 × 53 × 4 3/4 in. (99.1 × 134.6 × 12.1 cm)

Credit LineCharles F. Smith Fund

Object number1963.04

On View

On viewCollections

- 19th Century Landscapes and the Hudson River School

- What is America?: School Tour