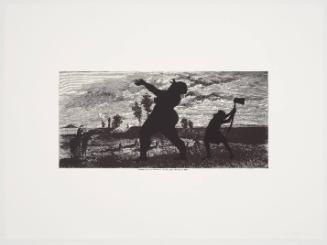

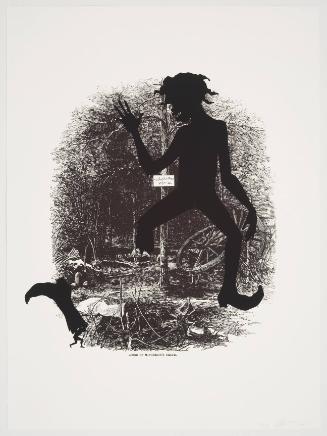

Skirmish in the Wilderness

Artist

Winslow Homer

American, 1836 - 1910

Date1864

MediumOil on canvas mounted on Masonite

DimensionsFrame: 25 1/2 × 35 1/2 × 3 1/4 in. (64.8 × 90.2 × 8.3 cm)

Image: 18 × 26 1/4 in. (45.7 × 66.7 cm)

Image: 18 × 26 1/4 in. (45.7 × 66.7 cm)

Credit LineHarriet Russell Stanley Fund

Object number1944.05

On View

On viewCollections

- 19th Century Genre, Academic Paintings & Sculpture

- What is America?: School Tour